Abstract

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is a systemic, autoimmune, inflammatory disease characterized by synovial hyperplasia, inflammatory cell infiltration in the synovial tissues, and progressive destruction of cartilage and bones. This disease often leads to chronic disability. More recently, activation of synovial fibroblasts (SFs) has been linked to innate immune responses and several cellular signalingpathways that ultimately result in the aggressive and invasive stages of RA. SFs are the major sources of pro-inflammatory cytokines in RA synovium. They participate in maintaining the inflammatory state that leads to synovial hyperplasia and angiogenesis in the inflamed synovium. The altered apoptotic response of synovial and inflammatory cells has been connected to these alterations of inflamed synovium. RA synovial fibroblasts (RASFs) have the ability to inhibit several apoptotic proteins that cause their abnormal proliferation. This proliferation leads to synovial hyperplasia. Apoptotic pathway proteins have thus been identified as possible targets for modifying the pathophysiology of RA. This review summarizes current knowledge of SF activation and its roles in the inhibition of apoptosis in the synovium, which is involved in joint damage during the effector phase of RA development.

Introduction

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune inflammatory disease that affects approximately 0.5% to 1% of the global population1. Synovial hyperplasia, which is the influx of inflammatory cells into synovial tissues, accelerates the destruction of bone and cartilage. The deterioration results in chronic pathology2, 3. Infiltrated immune cells cause degradation of the surface and extracellular matrix of the articular cartilage, cause bone erosion, and reduce the quality of life4, 5. The exact cause of RA is elusive. More recently, it has been demonstrated that the advancement of the disease solely relies on the activity of synovial fibroblasts (SFs) or rheumatoid arthritis specific synovial fibroblasts (RASFs) in the RA synovium2. In the RA synovium, the innate immune response and a few cellular signaling mechanisms mobilize the SFs that ultimately induce their aggressive and invasive behavior2, 6, 7. SFs provide the most important supply of pro-inflammatory cytokines in RA synovium, along with several growth factors that facilitate the prolonged inflammatory state7, 8, 9 . The latest findings elucidate the role of several inhibitors of growth factors that can inhibit the proliferation of the SFs that may result in synovial hyperplasia and promote angiogenesis within the inflamed synovium10, 11. The altered apoptotic response of synovial and inflammatory cells has been connected to these specific alterations of the inflamed synovium in RA12, 13, 14, 15. Contemporary RA studies focus on the chronic accumulation of osteoclasts and inflammatory cells in the RA synovial joints due to altered apoptosis. Furthermore, several apoptotic proteins have been identified as potential targets for modifying RA pathogenesis16, 17, 18. In this review, we have summarized the recent knowledge on SF-activation and SF-mediated mechanisms of inhibition of apoptosis inside the synovium involved in joint damage over the course of the effector phase of RA development.

Epidemiology of RA

Population-based studies have indicated that RA has a global prevalence of roughly 0.5% to 1% among adults1. According to the Global Burden of Disease study in 2010, the reported prevalence rate of RA is 0.24%, and females have twice the prevalence rate as males19, 20. However, according to a recent meta-analysis, the RA prevalence rate increased from 0.24% to 0.46% between 1980 and 201821. It was found in another study that the prevalence rate increased to 0.56% between 1980 and 201922. The prevalence rate of RA is much higher in Australia; the next highest prevalence rates are in North America and Europe. There is a relatively lower prevalence in several Asian countries19, 23. Another cross-sectional study reported that the prevalence rate of RA is 0.34% in the Indian population; however, it varies from 0.28% to 0.7% in the Indian population24, 25. These variations between regions and countries may exist as a result of differing methodological approaches as well as potential genetic and environmental risk factors. In the United States, 1 in every 12 women and 1 in every 20 men develops a rheumatic disease at some point in their lives26. Under post-COVID-19 pandemic circumstances, a UK-based population study reported that RA patients had an increased mortality rate during the pandemic compared to their pre-pandemic mortality rates, and the mortality risk was more prevalent in women27.

Normal Synovial joint

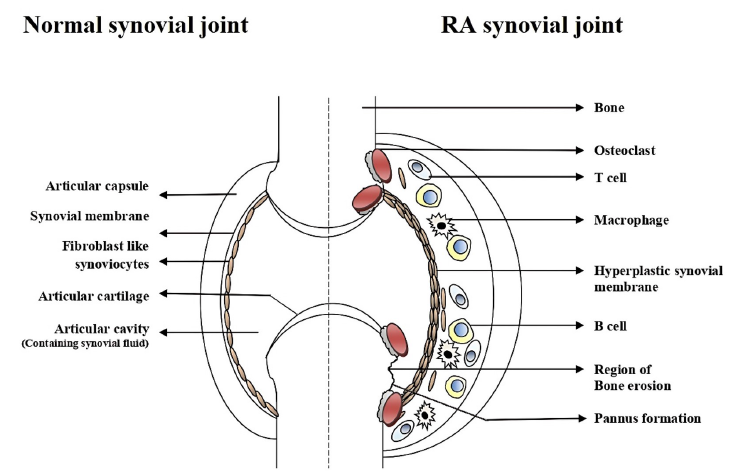

A key structural feature of a synovial joint is the presence of two components: the synovial fluid and the surrounding soft connective tissues, the articular cartilage, capsule, and ligaments (Figure 1). The articulating surfaces of the bones make contact with each other in this fluid-filled space. The articulating bony surfaces in the synovial joints move efficiently over each other and allow the bones to move smoothly against one another, which enables seamless joint mobility28.

The joint provides the infrastructure that facilitates mobility. The synovial membrane encases the joints, providing structural support (via a fibrous capsule), lubrication, and nutrients to the cartilage. The walls of the synovial cavity are formed by a fibrous connective tissue just outside the area of the bones’ articulating surface, the articular capsule, and the thin synovial lining membrane28. The cells of this membrane secrete a slimy synovial fluid that provides lubrication and nutrients to articular cartilages (Figure 1).

Synovial fluid consists of two types of cells: macrophage-like synovial cells (or Type A cells) and fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) (or Type B cells)29, 30. In normal synovium, type A cells are located in the intimal and sub-intimal regions and are mainly derived from the blood monocyte-macrophage lineage with characteristic Golgi apparatuses and dense vacuoles29. These cells are spherical, located at the upper part of the synovium surface, and migrate to the synovial membrane, where they remain resident cells30. Subintimal regions of normal synovium contain thin-walled lymphatic vessels. These vessels may be involved in leukocyte trafficking in the normal synovium31. The Type A synovial cells express Fc-gamma immunoglobin receptor (FcγR) and are positive for CD68 and CD 16328. These cells express major histocompatibility class II molecules (MHC-II). During the early stages of the immune response, they play an important role in antigen presentation. The type A cells can absorb and degrade extracellular constituents, cell debris, microorganisms, and many antigens within the synovia32.

Type B synoviocytes are the predominant cellular types found within the synovium. These cells are similar to fibroblast cells in that they express type IV and V collagens, vimentin, and the CD90 marker28, 30. They have rough endoplasmic reticulum throughout their cytoplasm, which indicates their prominent role in active protein trafficking within the synovia30, 32. Within the synovial lining, FLS synthesize uridine diphosphoglucose dehydrogenase (UDPGD), a key enzyme for the synthesis of hyaluronan30. FLS also release lubricin, which aids in joint-lubrication33. Cell adhesion molecules, such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), intracellular adhesion molecules-1 (ICAM-1), integrins, and the CD55 marker, are also expressed in both the intimal and sub-intimal regions of the synovium30. VCAM-1 is vital in cellular trafficking; the CD55 marker completely differentiates FLS (type B) from the type A macrophages28.

RA synovium

The prominent hallmark of RA is local and systemic inflammation initiated by the infiltration of immune cells2. There are two primary tissue layers in the RA synovium: the membrane lining (or intima) and the sub-intima30. RA significantly alters the structures of both areas (Figure 1). The T lymphocytes represent 30 — 50% and the B lymphocytes constitute about 5% of the sub-lining cells3. The proliferation of blood vessels and lymphoid aggregation is common in the intimal and subintimal areas of the inflamed synovium due to the hypoxic conditions34. Along with inflammatory cells such as neutrophils and lymphocytes, rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts (RASF) or rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes (RA-FLS) or type B synoviocytes modulate numerous pro-inflammatory pathways inside the rheumatoid joint8, 35. The macrophage-like cells have an extremely activated makeup and elaborate an array of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors that stimulate RASFs3. RASFs in the synovium lining layer display many signs of cellular activation, which leads to aggressive and invasive behavior3. In primary culture, synovial cells can escape the contact inhibition and can grow in an anchorage-independent manner over multiple passages36. The ability of activated RASFs to adhere to articular cartilage and to deeply penetrate the extracellular matrix through controlling gene expression is associated with the cartilage destruction and is the most prominent trait9, 35. Even in the absence of pro-inflammatory cytokines, the activated RASFs can maintain their aggressive and invasive behavior; such activity causes long-term structural alteration within the disease joints3.

Activation of RASFs in RA

Modulation of innate immunity

The activation of the innate system results in an upregulation of effector molecules involved in the aggressiveness of RASF even before clinical signs and symptoms appear. Microbial fragments can stimulate RASFs via the Toll-like receptors (TLRs), a conserved pattern recognition receptor (PRR) system37, 38. TLRs play a critical role in the early innate immune response in the face of invading microbes by sensing preserved pathogen structural patterns called PAMPs (Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns) or alterations in DAMPs (Danger-Associated Molecular Patterns) emitted from dead or dying cells37. Several TLR (TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, and TLR7) expressions have been discovered in RASFs out of the now 12 well-known TLRs in humans38. RASFs from the patients display high levels of specific TLR2, TLR3, and TLR4, and their stimulation triggers the production of IL-6 and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)39, 40. RASFs also produce a wide range of pro-inflammatory cytokines and effector molecules and exhibit a prominent pathogenic function during RA progression35. When stimulated by the appropriate PAMPs/DAMPs, RASF-TLRs initiate a number of signaling cascades, resulting in the activation of the Nuclear Factor Kappa Beta (NF-κB) and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) pathways, including c-Jun N-terminal kinase (c-JNK) inside the disease joints. This promotes the synthesis and upregulation of several pro-inflammatory cytokines [such as Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1, and IL-12], Type I interferon (Type I IFN) and numerous MMPs35, 41. Some of the genes regulated by activated NF-B include TNF-, IL-6, IL-8, inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS), and Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)36. RASFs are linked to COX-2 systems; these systems, along with other cellular signaling pathways, are involved in the regulation of synovial inflammatory pathways. TLRs are crucial to the modulation of the innate immune phases of RA development in RASFs.

Role of growth factors

Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) is an important stimulant for RASFs8. FGF-2 mRNA and FGF-2 proteins have been found in the pannus of RA patients, which indicates that FGF-2 is heavily involved in promoting cartilage and bone degradation, in addition to synovial hyperplasia42. Recent cell culture studies show that human RASFs are fundamental sources of FGF-2 in RA, and along with IL-17, it promotes the pathogenesis of autoimmune arthritis8. FGF-2 has an impact not only on the proliferation of RASFs but also on the induction of bone resorption by activating mature osteoclasts in a cultured cell line system43. FGF-2 also induces telomerase activity in cultured RASFs. Patients with RA have higher telomerase activity in their peripheral blood lymphocytes than healthy individuals44. The expression of various telomerase-related factors, such as Telomere Repeat-binding Factor-2 (TRF2) or the human telomerase RNA gene (hTERC), is also capable of modulating the telomerase activity in cultured RASFs, even when they are induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα45. Collectively, these studies indicate that FGF-2 has a direct role in upregulating the telomerase activities in cultured RASFs, which may suggest the proliferative nature of RASFs.

Another significant growth factor involved in the proliferation of RASFs is Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β). TGF-β1 is a multi-functional cytokine that promotes angiogenesis and regulates cellular development. Studies demonstrate that RASFs exhibit a high level of TGF-β expression39. According to a recent study, the stimulatory effect of TGF-β enhances the MMP2 expression in RASFs. TGF-β causes epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in RASFs by activating the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway, which ultimately contributes to the migratory phenotypes of RASFs39. Multiple recent studies reveal that a ubiquitous phosphatase, non-receptor Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 14 (PTPN 14), and a tumor-promoting transcription co-activator, Yes-Associated Protein (YAP), promote TGF-β-dependent SMAD3 nuclear localization in RASFs. This may also promote the pathogenic behavior of the RASFs in relation to synovial hyperplasia46. Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF) is another strong stimulator of RASFs. Numerous isoforms of it can be expressed within the RA synovium47. In RASFs, PDGF causes the loss of contact inhibition and anchorage-independent growth36. A recent study indicates that the phosphorylation of PDGF receptors (PDGFR) along with TGF-β co-operation triggers the formation of matrix-degrading invadosomes in RA synoviocytes48.

Activation by NF-κB pathway

One of the key phases concerning RASFs’ proliferation is the NF-κB activation pathway49, 50, 51. It plays an important role in the inflammatory pathway by controlling the expression of many pro-inflammatory gene clusters. This transcription factor is dimeric in nature, formed by p50 and p65 subunits; however, several combinations with alternative subunits happen conjointly. Normally, a class of inhibitory proteins called inhibitor of NF-κB kinases (IKKs) sequesters transcription factor NF-κB proteins within the cytoplasm, which masks the nuclear localization sequence of NF-κB dimers and holds them in an inactive state in the cytoplasm51. Activation of NF-κB needs diverse stimuli, including ligands of various cytokine receptors, PPRs, or TNF receptors (TNFRs), as well as B-cell receptors (BCRs) and T-cell receptors (TCRs)51. Phosphorylation of IKK occurs in response to stimulation, which is an important step in NF-κB activation (Figure 2). Two kinase subunits, IKKα (IKK1) and IKKβ (IKK2), and a regulatory subunit, IKKγ (NEMO), comprise the IKK complex51. Phosphorylation of the inhibitory subunits releases the NF-κB dimers and allows the dimers for nuclear translocation, where they attach to the target gene’s promoter50, 51. The NF-κB signaling pathway is activated by two mechanisms. The canonical route is activated by a variety of stimuli, including lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF- and IL-1, PPRs, and growth factors. Alternatively, certain stimuli, such as B-cell-activating lymphotoxin or CD40 ligand (CD40L), can activate the non-canonical pathway52. However, the activation of NF-κB dimers depends on the phosphorylation and processing of precursor protein p100 in the non-canonical pathway. Both pathways cause the translocation of NF-κB dimers to the nucleus in order to induce NF-κB-targeted gene transcription52.

Both IKK1 and IKK2 are constitutively expressed by RASFs. Activation of the IKK complex results in sequential degradation of IκB and accelerated NF-κB nuclear binding; however, IKK1 is the key molecule for NF-κB activation in RASFs49. There is recent evidence that microRNA-10a (miR-10a) also accelerates the IκB degradation pathway in RASFs6. As a result, NF-κB is released and reaches the nucleus of RASFs, where it binds to the Ying Yang 1(YY1) promoter and upregulates its expressionFigure 2. The YY1 protein also functions as a transcription factor, repressing miR-10a expression by binding to the miR-10a promoter region. Downregulating miR-10a expression promotes NF-B activation, which results in the production of a large amount of cytokines (TNF-, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8) and MMPs6. NF-κB additionally activates a vast spectrum of downregulating genes and effector molecules (such as COX-2) that further contribute to synovial proliferation and inflammation16. Bioactive plant components such as paeonol inhibited both the NF-κB p65 subunit phosphorylation and IκB degradation in a cell culture-based study53. According to an additional study, icariin (a potent and bio-active phytocomponent from Epimedium) can inhibit TNF-α stimulated RASF proliferations in a concentration-dependent manner by inhibiting the TLR2/ NF-κB pathway54. According to an additional recent study, several phenolic constituents can inhibit the IκB degradation and phosphorylation NF-κB p65 subunit at the protein level in a TNF-α stimulated human RASF cell line55. These findings illustrate the potential of NF-κB signaling pathway modulation as a future therapeutic agent for RA progression.

Role of MMPs and matrix degradation

MMPs constitute 5 subfamilies of enzymes that conjointly degrade all extracellular matrix components56. Collagenases (MMP-1, MMP-13), stromelysins (MMP-3), and membrane type (MT) MMP-14 are abundantly expressed within the RA synovium56, 57. Multiple components, including pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, growth factors, NF-κB, and TLR ligands, activate their synthesis and expressions in the RASFs53, 57. Within the RASFs, MT1-MMP (MMP-14) is the most important MMP related to cartilage destruction58. MT1-MMP performs a crucial role in the aggressive makeup of RASFs, is enormously expressed on the RA synovium, and is accountable for the invasion of RASFs into cartilage58.

Tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs), a physiologic inhibitor produced by synovium chondrocytes and fibroblast cells, tightly regulate MMP gene expression in RASFs56. All TIMPs can inhibit all the MMPs through non-covalent interactions involving a conserved cysteine residue at position 1, which raises the possibility of targeting TIMPs as therapeutic agents56. However, the normal amounts of TIMPs found in RA joints, are insufficient to counteract the matrix-degrading effects of MMPs and cathepsins59. A study involving a canine RA model has demonstrated decreased synovial TIMP-1 expression in comparison to MMP-3 level59. However, the over-expression of the TIMPs may have the beneficial effect of decreasing the RASF-mediate cartilage destruction60. It has been reported in a cell culture study that the treatment with anti-malarial drugs such as artesunate can increase the mRNA and protein expression of TIMP-2, in contrast to MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression, in a dose-related manner60. These studies could lead to possible therapies targeted at the RASF-mediated joint-destructive events in RA. In addition to MMPs, cathepsin K, produced through RASFs, contributes extensively to the degrading processes and the resorption of bones inside the rheumatoid joints61, 62. The cathepsin family contains eleven members of proteinases, among which cathepsins B, H, K, L, and S are the notable proteolytic enzymes capable of degrading native collagens and other components of the ECM63. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 can stimulate cathepsin K expression in murine cell lines64. Cathepsin B also promotes TIMP degradation in RA patients and activates PDGF-mediated migration and invasion of RASFs via MAPKs and c-JNK65, 66. In anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA)-positive RA patients, it has been found that the cathepsin K concentration increases in bone marrow samples more than in the peripheral blood. This suggests the local production of the protease enzyme62. In summary, it is well documented that RASFs are the prominent effector cells in producing MMPS and cathepsins that stimulate the progressive degradation of cartilages and bone, which might be the primary hallmarks of RA.

Hypoxia and angiogenetic factors

Hypoxia is another prominent feature that triggers RASFs’ involvement in increased synovitis, angiogenesis, bone erosion, and cartilage destruction in RA pathogenesis. In RA patients, Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE), which catalyzes the synthesis of angiotensin II from its inactive precursor, angiotensin I, is elevated in RASFs67. Increased tissue ACE can raise the angiotensin II concentration, which leads to synovial hypoxia67. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is one of the key regulators of synovial tissue hypoxia68. In normal conditions, HIF-1α protein is hydroxylated by oxygen-dependent prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) protein and by factors inhibiting HIF-1α (FIH1) protein. These factors inactivate NF-κB transcriptional activation and cause degradation of HIF-1α68, 69. In hypoxic conditions, PHD activity reduces, which permits HIF-1α to phosphorylate the IKK subunits; this leads to the activation of NF-κB-induced gene expression68. In RASFs, HIF-1α promotes IL-8, MMPs, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression, which lead to cartilage destruction and angiogenesis70. When synovial tissues from RA patients are cultured in a hypoxic environment, they had elevated amounts of MMP-1 and MMP-3 expression and relatively low levels of TIMP-1 expression71. Consequently, over-expression of HIF-1α causes significant up-regulation of MMPS in cultured RASFs, which may lead to the cartilage invasion72. Furthermore, suppression of HIF-1α by RNA interference (RNAi) also suppresses the MMP-13 expression in cultured RASFs, which confirms the direct regulation of HIF-1α-induced MMP-13 expression72. Inducing HIF-1α through TLR signaling increases the production of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α), MMPs (MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-9), and VEGF contributes to the progression of RA73. In a recent study of a collagen-induced arthritis Wistar rat model, researchers found that inhibiting HIF-1α using RNAi reduces the expression of inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-6, IL-1, and TNF-α) in both synovial cell culture and peripheral blood serum69.

To restore oxygen delivery to the RASFs’ tissue, angiogenesis is initiated as a part of the cellular adjustments. The increased blood supply is critical for transporting immune cells to the site of inflammation and providing nutrition to the pannus74. VEGF is a key regulator of angiogenesis in RASFs70. A positive feedback regulation between HIF-1α and VEGF triggers angiogenesis in hypoxic conditions68, 73. Both HIF-1α and HIF-2α can stimulate VEGF expression in the RASFs65. In addition to HIF1-α and VEGF, pro-inflammatory mediators can also promote angiogenesis in RASF. This promotion leads to the expression of cytokines (IL-6, IL-8), chemokines (CXCL10, CXCL17), MMPs (MMP-1), and adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, VCAM-1), which may trigger the synovial cellular infiltration and invasive behavior of the RASFs73, 75. According to a recent study, Antcin K (a phytosterol isolated from Antrodia cinnamomea, medicinal mushroom) significantly inhibited VEGF expression in cultured RASFs by downregulating the phospholipase C(PLC)-γ and protein kinase C (PKC)-α pathway76. These findings imply that hypoxia has an important role in promoting angiogenesis, cell infiltration, cartilage damage, and disease progression. They also imply that targeting HIF1 and VEGF could be a novel strategy for future medication for RA.

RASFs and matrix degradation

The control of osteoclastogenesis by RASFs influences bone erosion77, 78. Receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK) and its ligand (RANKL), a TNF receptor-family protein, initiate the bone-degrading pathway, osteoclast development, and bone resorption78. RANK is highly expressed in osteoclast precursor cells, mature osteoclasts, dendritic cells, and synovial fibroblasts77, 78. When the RANK pathway is activated, monocyte-macrophage progenitor cells become osteoclasts, and mature osteoclasts become able to activate79. RANK activates different intracellular signaling cascades in response to RANKL-stimulation by interacting with Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor-Associated Factors (TRAFs). In particular, TRAF6 leads to the activation of its downstream pathway, which includes rapid activation of MAPKs, NF-κB, and activator protein-1 (AP-1)79.

Inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, IL-22 can also modulate the RANKL expression in RASFs. This expression promotes further proliferation of RASFs11, 80, 81. C-reactive proteins (CRP), biomarkers for the assessment of RA progression, also have stimulatory effects on RANKL production, which was observed in the synovial fluid and serum samples obtained from RA patients82. RANKL mRNA has been found in the synovial lining layer of RA patients and in the synovium of rats in both collagen-induced and adjuvant-induced arthritis83, 84. The expression of RANKL mRNA increased when RASFs were stimulated by VEGF85. Another study indicated that the selective secretion of IL-17 cytokine from Type 17 helper T cells (Th17) can stimulate RANKL production in cultured RASFs at both the gene and protein levels77. The expression pattern of RANKL mRNA increased in a dose-dependent manner when cultured RASFs were stimulated with varying dosages of IL-1777. However, a recent study demonstrated that pre-treatment of RASFs with IL-25 can decrease osteoclastogenesis by reducing IL-22-induced RANKL expression at the mRNA level86. Pentraxin 3, an acute phase protein, also inhibits FGF-2-induced osteoclastogenesis in cultured synovial tissues from RA patients by reducing RANKL expression and then suppressing other inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α11. In the collagen-induced arthritis mice model, intraperitoneally injecting Pentraxin 3 also significantly decreases the RANKL protein level for both the serum and the synovial tissues11. These findings suggest the pivotal influence of RASFs on osteoclastogenesis in terms of the RANK/RANKL pathway. Focusing on RANKL could demonstrate therapeutic potential.

RASFs and Resistance to Apoptosis

The resistance of cell-death is a key issue that modulates uncontrolled aggressive growth in RASFs12, 13. The synovial tissue acquired from the RA patients displays synovial lining hyperplasia in sub-lining layers due to the accumulation of macrophages and synovial fibroblasts13. These cells enhance the joint inflammation and swelling, which is mainly mediated by the accumulation of several of pro-inflammatory cytokines. TNF-α and interleukin IL-1, chemokines such as IL-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, and proteinases such as MMPs and cathepsins are examples of the pro-inflammatory cytokines that accumulate66, 72, 87. Activated osteoclasts immediately promote RANKL-mediated joint destruction by destroying the adjacent bone at the synovial-bone-cartilage interface (Figure 1 )78, 79. Within the sub-lining region, there may be an accumulation of persistent inflammatory cells, which contains lymphocytes and macrophages3. At the molecular level, RASFs are characterized by the activation and modulation of signaling pathways. NF-κB signaling results in the overexpression of adhesion molecules, imbalanced expression of matrix-degrading enzymes, and alterations in cell death6, 56. Despite the fact that the molecular basis of synovial hyperplasia remains unknown, an increasing amount of data indicates that RASFs are resistant to cell death. The processes of the development and persistence of RA in synovium remain unknown. Insufficient cell death of synovial macrophages (along with fibroblasts and lymphocytes) could be one of the factors contributing to its prognosis3, 12. There appear to be numerous mechanisms in RASF that mediate the over-expression of matrix-degrading enzymes and cell death resistance.

Modulation of FAS death-receptor mediated apoptosis on RASF

The apoptosis signaling cascade can be triggered by death receptors or mitochondria-dependent mechanisms. The ligation of death receptors initiates a death-receptor-dependent pathway. Fas, the TNF-Related Apoptosis Inducing Ligand (TRAIL) receptors, R1, and R2 are the most common death receptors. These cell death receptors cause cell death when ligated with the Fas ligand (FasL) or TRAIL88. After the suppression of NF-κB, ligation of TNF receptor-1 with TNF-α may trigger cell death cascades. Following FasL ligation, FADD (Fas-Associated via Death Domain) forms a Death-Inducing Signaling Complex (DISC) with pro-caspase-8; the formation causes caspase-8 activation via proteolytic cleavage88. Another example is a TNF-ligand binding to a TNF receptor, which ensues when TNF Receptor-type-1-Associated Death Domain protein (TRADD) and receptor-interacting protein (RIP) are recruited to activate pro-caspase-8 via auto-proteolytic processing88. The execution pathway is initiated once caspase-8 is activated (Figure 3).

Both Fas and FasL are expressed by macrophages in the joints of RA patients89. Other cells in the joint, such as lymphocytes and synovial fibroblasts, also express Fas13. There have been multiple investigations regarding the process that contributes to Fas-mediated cell death resistance in RA89, 90, 91. FLICE-inhibitory protein (FLIP), an endogenous anti-apoptotic protein, can inhibit death receptor-mediated apoptosis by binding to pro-caspase-8 and blocking its connection with FADD89. Despite their high expression of Fas, results demonstrate that both the native RASFs and cultured RASFs are resistant to Fas-mediated apoptosis in the synovial tissue of RA patients90. FLIP expression was elevated inside the synovial lining and pannus of the ankle joints in the adjuvant-induced arthritis (AIA) rat model of RA beginning on day 14 and persisted in the pannus throughout the disease progression91. Consistent findings indicate that FLIP mRNA expressions in synovial fibroblasts are 50 percent higher in RA than in OA90. While synovial tissues had been examined by immunohistochemistry, there is evidence that excessive expression of FLIP was related to low levels of apoptosis in early RA16. This study suggests that the downstream expression of FLIP may suppress the extrinsic pathway of apoptosis in RA synovial joints (Figure 3). Proteins involved in post-translational modifications also play pivotal role in Fas-mediated apoptosis in RASFs92. Small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO)-1, a key regulator protein in the post-translational pathway, can also alter FADD-mediated apoptosis in cultured RASFs by recruiting the transcriptional repressor protein DAXX92. These studies indicate the extrinsic pathway of cell death may be inhibited by downstream regulation of FLIP proteins in RA synovial joints.

Modulation of Bcl-2 and IAP mediated apoptosis on RASF

Non-receptor-mediated events, such as DNA damage, growth factor withdrawal, or loss of interaction with the extracellular matrix, activate the intrinsic signaling pathway. This activation leads to apoptosis. These stimuli cause intracellular signals to be produced, which immediately cause negative or positive changes at the cell’s targets. Activation of this pathway alters the mitochondrial membrane integrity; there is a loss of mitochondrial transmembrane capability and a release of numerous pro-apoptotic proteins that include: Apoptosis-Inducing Factor (AIF), cytochrome c, and Second Mitochondrial Activator of Caspases (SMACs)93. Depending on various apoptotic stimuli, those pro-apoptotic molecules that are activated end up in the mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization; this region successively releases various inter-membrane proteins together with cytochrome c. The proteins facilitate the formation of the apoptosome. Within the apoptosome, activated procaspase-9 is converted to caspase-9. Caspase-9 triggers caspase-3, resulting in cell death93. Members of the B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) family of proteins, which govern cytochrome c released from the mitochondria, control and regulate those events in the intrinsic route93. Under normal physiological conditions, Bcl-2 is a group of cytoplasmic proteins that enhance cell viability to maintain cellular homeostasis. These proteins are found in the outer mitochondrial membrane and are necessary for maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis and avoiding apoptosis. Anti-apoptotic [Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, A1, and myeloid-cell leukemia sequence 1 (Mcl-1)] and pro-apoptotic (Bax, Bak, and Bid) proteins are in the Bcl-2 family; these proteins enable cell survival by altering mitochondrial integrity93. The persistent infiltration of T-cells and hyper-proliferation of RASFs could be indicators of disease progression. Continuous stimulation of T-cells with lymphokines, such as IL-1, or byproducts of activated fibroblasts can prevent apoptosis by maintaining high amounts of Bcl-2 family proteins, specifically Bcl-xL12. The exaggerated expression of the Bcl-2 family of proteins (which includes Bcl-2, Mcl-1, and Bcl-xL) contributes to high numbers of RASFs and inflammatory cells inside the RA synovium94. As a result, the synovial lining thickens, and the inflammation continues to progress.

The Bcl-2 family of proteins regulates the apoptosis pathway in osteoclasts. They have a direct role in the mitochondrial release of cytochrome c, which activates caspase-3 and caspase-994. In RA, Bcl-2 expression is higher in synovial tissues than in OA94. High amounts of Bcl-2 proteins have also been observed in the ankle joints of AIA rat models91. However, NF-κB regulates Bcl-xL overexpression. This regulation may contribute to the prevention of apoptosis in macrophages and RASFs94. Many studies have investigated the possible mechanisms that lead to the increased expression of Bcl-2. A cell-culture-based study in human synoviocyte has demonstrated that RASFs induce IL-15 elevation within the RA synovium, and it contributes an anti-apoptotic property95. Exogenous IL-15 increases the expression of Bcl-xL mRNA in cultured RASFs95. Furthermore, inhibiting endogenously generated IL-15 has caused apoptosis by suppressing the expression of both Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL95. While the specific mechanism of action of Bcl-2 proteins in RA is unknown, Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL are suspected to play a major role in inhibiting the apoptosis of various cell types within the synovial joints of RA patients (Figure 3). Therefore, inhibiting the action of Bcl-2 anti-apoptotic proteins can be useful in reducing inflammation and joint erosion in RA patients. For this reason, it has been suggested as a treatment for RA.

Several natural and synthetic chemicals have the ability to imitate the Bcl-2 homology 3 (BH3) domain, which could block its anti-apoptotic action. These chemicals target the BH3 domain, which is present in all pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins as well as anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 proteins. To disseminate the apoptotic signal and promote activation of the Bcl-2 pro-apoptotic molecules Bax and Bak, the BH3 protein initiates apoptosis in response to a range of cellular events96. A recent study has reported that a plant derived pentacyclic triterpenoid, ursolic acid (UA) can induce apoptosis in cultured RASFs by inducing Noxa (members of BH3) expression and proteasomal degradation of Mcl-117. When cultured RASFs are treated with UA, Noxa expression is followed by a dose-dependent reduction in Mcl-1 expression17. As a result, these chemicals may be useful in the treatment of RA, as BH3-only pro-apoptotic proteins are anticipated to play a protective role in the destruction of the RA joint (Figure 3). Gallic acid, a polyphenolic acid found in nature, can cause apoptosis in RASFs by regulating the expression of apoptosis-related proteins and decreasing the expression of pro-inflammatory genes97. Since hypoxia could be a regulator of apoptosis and is generally pro-apoptotic, in some cases, brief or repetitive exposure to hypoxia may increase cells’ resistance to apoptosis via the mitochondrial Bcl-2 pathway98. Hypoxia induces the pro-apoptotic protein Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19-kd protein–interacting protein 3 (BNIP-3) within RASFs, and studies indicate that it is broadly expressed within the RA synovium99. Over-expression of BNIP3 in RASFs can increase apoptosis in the RA synovium by inhibiting several anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins99. In cultured RASFs, another growth factor protein, NK4, inhibits NF-κB signaling by decreasing Bcl-2 protein levels, raising Bax and caspase-3 protein levels, and decreasing Bcl-2 protein levels100. A recent cell culture study has demonstrated that the chemical inhibition of heat-shock protein 90 (HSP90) by geldanamycin causes the suppression of TNF-α-induced proliferation of cultured RASFs in a dose-dependent manner, modulating the NF-κB signaling pathway101. Furthermore, geldanamycin also induces apoptosis in cultured RASFs in a dose-dependent manner by decreasing Bcl-2 expression and increasing the expression of Bax101. These findings reveal the potential mechanism underlying the function of Bcl-2 family proteins in inducing apoptosis in RASFs; this insight might be beneficial in reducing synovial hyperplasia.

The IAP protein family, which inhibits both upstream and downstream caspases, is another essential protein family93. These proteins also have a role in cell cycle regulation and immunological functions. In addition, they stimulate immune cells such as macrophages, T-cells, and B-cells102. In the human genome, eight separate IAP genes have been identified, with XIAP being the most extensively characterized. It has three BIRs, a ubiquitin-binding domain (UBA), and one zinc finger-like RING, all of which can bind to caspases-3, 7 and 9 and block their proteolytic activity when combined with adjacent residues103. Because BIR3 binds to caspase-9 and BIR2 binds to caspases-3 and 7, XIAP inhibits caspases by binding directly to them. As a result, XIAP is the most convenient mammalian IAP protein that can directly inhibit caspases by binding to their active catalytic sites103. Further studies have revealed that IAPs are critical regulators of immune-cell death in RA in addition to inflammation in general102, 104. XIAP expression has been observed in RA, and this is due to CD68-positive macrophage cells within the RA synovium102. Survivin functions similarly to XIAP in that it inhibits each of the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways directly or indirectly105. Survivin reduces apoptosis via binding to caspase-9 or by blocking SMAC (a pro-apoptotic protein that binds IAPs), preventing caspases from inhibiting each other106. As a consequence, it prevents the pro-apoptotic protein from blocking IAP proteins (Figure 3).

Survivin expression in RASFs has been frequently studied107, 108. The concentration of survivin in RASFs and its plasma level have a strong positive correlation107. High survivin concentrations were found to increase the overall risk of RA progression in ACPA-positive patients in a population-based investigation108. The phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)-protein kinase B (Akt) signaling system regulates survivin expression in RASFs via the NF-κB, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2) signaling pathways105. Few cytokines, like IL-6, can induce the PI3K/Akt pathway that ultimately triggers survivin expression in RASFs18. Survivin levels in serum and cultured cell supernatants are significantly higher in smoker RA patients than in non-smoker RA patients109. The levels of survivin from serum and cultured cell supernatants are much higher in smoker RA patients than in non-smoker RA patients109. This is due to nicotine's ability to stimulate nicotinic receptors, which causes CD8+ T cells to develop a non-exhausted phenotype. The development of this phenotype increases the expression of survivin in RA patients who smoke109. Survivin is also implicated in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 and other MMPs in RA patients, and it promotes tumor-like growth of RASFs18. Over-expression of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), an antagonist of survivin, can inhibit both RASF-mediated migration and IL-6 production in cultured cells18. Thus, over-expression of survivin and XIAP contributes to the maintenance of synovial hyperplasia in RASFs by inhibiting the apoptosis of cells within the synovial joints (Figure 3). Embelin (2, 5-dihydroxy-3-undecyl-1,4-benzoquinone), another naturally occurring alkyl substituted hydroxybenzoquinone that is an active ingredient of the fruit Embelia ribes110, is a cell-permeable non-peptide small molecule XIAP inhibitor. Embelin possesses anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, and analgesic effects, according to research111. A mouse model of collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) demonstrates that collagen strongly suppresses inflammation and bone erosion112. The therapeutic effects of embelin have been demonstrated in a mouse model of inflammatory arthritis. There must be further research to determine its precise mechanism of action as well as cellular targets. As a result, controlling the hyperplastic RASF may require modifying the IAP family of molecules in future studies.

Conclusions

The understanding of the role of RASFs in the etiology of RA has progressively improved over the years. The accumulation and infiltration of several inflammatory cells and the activation of RASFS within the RA synovium play a crucial role in RA pathogenesis. In the synovium, they actively participate in modulating several pro-inflammatory pathways that, in the course of disease progression, cause bone erosion. In the RA synovium, RASFs have the ability to inhibit several apoptotic proteins that cause their abnormal proliferation, which leads to the highly invasive effects of synovial hyperplasia. Several observations in RA patients and in animal models suggest that enhanced apoptosis may be therapeutically beneficial in RA treatment. As a result, current research focuses on discovering specific treatments that can stimulate apoptosis in inflamed synovium. However, until now, no clinical trials have been conducted using therapeutics that target apoptosis in RA synovium through the inhibition of intracellular apoptotic inhibitory molecules. A better understanding of the mechanisms that regulate RASF activation and their inhibition of apoptosis within the inflamed synovium will allow for more effective treatment for RA patients. This review proposes future studies that could investigate these complications in treating this degenerative and inflammatory joint disease.

Abbreviations

ACE: Angiotensin converting enzyme, ACPA: Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, AIA: adjuvant-induced arthritis, AIF: Apoptosis-Inducing Factor, Akt: Protein kinase B, Bcl-2: B-cell lymphoma 2, AP-1: Activator protein-1, BCR: B-cell receptors, BH3: Bcl-2 homology 3, BIRs: Baculovirus IAP repeats, BNIP-3: BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19-kd protein-interacting protein 3, CIA: Collagen induced arthritis, c-JNK: c-Jun N-terminal Kinase, CL40L: CD40 ligand, COX-2: Cyclooxygenase-2, DAMPs: Danger-Associated Molecular Patterns, ECM: Extra cellular matrix, EMT: Epithelial mesenchymal transition, FADD: Fas-associated via Death Domain, FasL: Fas Ligand, FGF: Fibroblast growth factor, FLIP: FLICE-inhibitory protein, FLS: fibroblast-like synoviocytes, HIF: Hypoxia-inducible factor, HSP90: Heat-shock protein 90, hTERC: Human telomerase RNA gene, IAPs: Inhibitor of apoptosis, ICAM-1: Intracellular adhesion molecules-1, IKKs: Inhibitor of NF-κB kinases, iNOS: Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase, IRAK: Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase, LPS: Lipopolysaccharides, MAPK: Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase, Mcl-1: Myeloid-cell leukemia sequence 1, MHC-II: major histocompatability class II molecules, miR-10a: micro-RNA-10a, MMPs: Matrix metalloproteinases, NF-κB: Nuclear Factor Kappa Beta, OA: Osteoarthritis, PLC: Phospholipase C, PKC: Protein kinase C, PAMPs: Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns, PDGF: Platelet derived growth factor, PDGFR: Platelet derived growth factor receptor, PHD: Prolyl hydroxylase domain, PI3K: Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase, PPRs: Pattern recognition receptors, PTEN: Phosphatase and tensin homolog, PTPN: Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase, RA: Rheumatoid arthritis, RA-FLS: Rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes, RANK: Receptor activator of NF-κB, RANKL: Receptor activator of NF-κB ligand, RASF: Rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblast, RIP: Receptor-interacting protein, RNAi: RNA interference, SDF-1: Stromal cell-derived factor 1, SFs: Synovial fibroblasts, SMACs: Second Mitochondrial Activator of Caspases, TCR: T-cell receptors, TGF-β: Transforming Growth Factor- β, TIMPs: Tissue inhibitors of MMPs, TLRs: Toll-like receptors, TNFR: TNF receptors, TRADD: TNF Receptor type 1 associated Death Domain protein, TRAF: Tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factor, TRAFs: Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Associated Factors, TRAIL: TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand, TRF2: Telomere Repeat-binding factor-2, Type I IFN: Type I interferon, UA: Ursolic acid, UBA: Ubiquitin-binding domain, UDPGD: Uridine diphosphoglucpse dehydrogenase, VCAM-1: Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor, XIAP: X-linked IAP, YAP: Yes-associated protein, YY1: Yang Yang 1

Acknowledgments

None.

Author’s contributions

SB conceptualized the idea behind this review manuscript. The original draft manuscript was prepared by DM and revised the manuscript. SB edited the final manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

-

Scott

D.L.,

Wolfe

F.,

Huizinga

T.W.,

Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet.

2010;

376

(9746)

:

1094-108

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

McInnes

I.B.,

Schett

G.,

The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. The New England Journal of Medicine.

2011;

365

(23)

:

2205-19

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Bartok

B.,

Firestein

G.S.,

Fibroblast-like synoviocytes: key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunological Reviews.

2010;

233

(1)

:

233-55

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

England

B.R.,

Thiele

G.M.,

Anderson

D.R.,

Mikuls

T.R.,

Increased cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis: mechanisms and implications. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.).

2018;

361

:

k1036

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

McFarlane

I.M.,

Zhaz Leon

S.Y.,

Bhamra

M.S.,

Burza

A.,

Waite

S.A.,

Rodriguez Alvarez

M.,

Assessment of cardiovascular disease risk and therapeutic patterns among urban black rheumatoid arthritis patients. Medical Sciences : Open Access Journal.

2019;

7

(2)

:

31

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Mu

N.,

Gu

J.,

Huang

T.,

Zhang

C.,

Shu

Z.,

Li

M.,

A novel NF-κB/YY1/microRNA-10a regulatory circuit in fibroblast-like synoviocytes regulates inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Scientific Reports.

2016;

6

(1)

:

1-14

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Jing

W.,

Sun

W.,

Zhang

N.,

Zhao

C.,

Yan

X.,

The protective effects of the GPR39 agonist TC-G 1008 against TNF-α-induced inflammation in human fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLSs). European Journal of Pharmacology.

2019;

865

:

172663

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Shao

X.,

Chen

S.,

Yang

D.,

Cao

M.,

Yao

Y.,

Wu

Z.,

FGF2 cooperates with IL-17 to promote autoimmune inflammation. Scientific Reports.

2017;

7

(1)

:

7024

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Lee

Y.S.,

Lee

S.Y.,

Park

S.Y.,

Lee

S.W.,

Hong

K.W.,

Kim

C.D.,

Cilostazol add-on therapy for celecoxib synergistically inhibits proinflammatory cytokines by activating IL-10 and SOCS3 in the synovial fibroblasts of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Inflammopharmacology.

2019;

27

(6)

:

1205-16

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Lee

C.J.,

Moon

S.J.,

Jeong

J.H.,

Lee

S.,

Lee

M.H.,

Yoo

S.M.,

Kaempferol targeting on the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3-ribosomal S6 kinase 2 signaling axis prevents the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Cell Death & Disease.

2018;

9

(3)

:

401

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Zhao

S.,

Wang

Y.,

Hou

L.,

Wang

Y.,

Xu

N.,

Zhang

N.,

Pentraxin 3 inhibits fibroblast growth factor 2 induced osteoclastogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy.

2020;

131

:

110628

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Firestein

G.S.,

Yeo

M.,

Zvaifler

N.J.,

Apoptosis in rheumatoid arthritis synovium. The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

1995;

96

(3)

:

1631-8

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Chou

C.T.,

Yang

J.S.,

Lee

M.R.,

Apoptosis in rheumatoid arthritis expression of Fas, Fas-L, p53, and Bcl-2 in rheumatoid synovial tissues. The Journal of Pathology.

2001;

193

(1)

:

110-6

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Lee

S.Y.,

Kwok

S.K.,

Son

H.J.,

Ryu

J.G.,

Kim

E.K.,

Oh

H.J.,

IL-17-mediated Bcl-2 expression regulates survival of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis through STAT3 activation. Arthritis Research {&}amp; Therapy.

2013;

15

(1)

:

31

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kim

E.K.,

Kwon

J.-E.,

Lee

S.-Y.,

Lee

E.-J.,

Moon

S.-J.,

Lee

J.,

IL-17-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction impairs apoptosis in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts through activation of autophagy. Cell Death & Disease.

2018;

8

(1)

:

e2565

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Jiao

Yc,

Huang

Ss,

Wan

Cy,

Liu

Yx,

Wang

Y.,

Bai

Yy,

CRT promoted c-FLIP expression via NF-κB pathway in rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Tianjin Yi Yao.

2018;

46

(2)

:

113-7

.

-

Kim

E.Y.,

Sudini

K.,

Singh

A.K.,

Haque

M.,

Leaman

D.,

Khuder

S.,

Ursolic acid facilitates apoptosis in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts by inducing SP1-mediated Noxa expression and proteasomal degradation of Mcl-1. The FASEB Journal.

2018;

32

(11)

:

fj201800425

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Chen

D.,

Liu

D.,

Liu

D.,

He

M.,

Peng

A.,

Xu

J.,

Rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocyte suppression mediated by PTEN involves survivin gene silencing. Scientific Reports.

2017;

7

(1)

:

367

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Cross

M.,

Smith

E.,

Hoy

D.,

Carmona

L.,

Wolfe

F.,

Vos

T.,

The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

2014;

73

(7)

:

1316-22

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

van Vollenhoven

R.F.,

Sex differences in rheumatoid arthritis: more than meets the eye. BMC Medicine.

2009;

7

(1)

:

12

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Almutairi

K.,

Nossent

J.,

Preen

D.,

Keen

H.,

Inderjeeth

C.,

The global prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis based on a systematic review. Rheumatology International.

2021;

41

(5)

:

863-77

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Almutairi

K.B.,

Nossent

J.C.,

Preen

D.B.,

Keen

H.I.,

Inderjeeth

C.A.,

The prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of population-based studies. The Journal of Rheumatology.

2021;

48

(5)

:

669-76

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Gonzalez

A.,

Maradit Kremers

H.,

Crowson

C.S.,

Nicola

P.J.,

Davis

J.M.,

Therneau

T.M.,

The widening mortality gap between rheumatoid arthritis patients and the general population. Arthritis and Rheumatism.

2007;

56

(11)

:

3583-7

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Chopra

A.,

Disease burden of rheumatic diseases in India: COPCORD perspective. Indian Journal of Rheumatology.

2015;

10

(2)

:

70-7

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Handa

R.,

Rao

U.R.,

Lewis

J.F.,

Rambhad

G.,

Shiff

S.,

Ghia

C.J.,

Literature review of rheumatoid arthritis in India. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases.

2016;

19

(5)

:

440-51

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Crowson

C.S.,

Matteson

E.L.,

Myasoedova

E.,

Michet

C.J.,

Ernste

F.C.,

Warrington

K.J.,

The lifetime risk of adult-onset rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Arthritis and Rheumatism.

2011;

63

(3)

:

633-9

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Peach

E.,

Rutter

M.,

Lanyon

P.,

Grainge

M.J.,

Hubbard

R.,

Aston

J.,

Risk of death among people with rare autoimmune diseases compared with the general population in England during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Rheumatology (Oxford, England).

2021;

60

(4)

:

1902-9

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Smith

M.D.,

The normal synovium. The Open Rheumatology Journal.

2011;

5

:

100-6

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Barland

P.,

Novikoff

A.B.,

Hamerman

D.,

Electron microscopy of the human synovial membrane. The Journal of Cell Biology.

1962;

14

(2)

:

207-20

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Firestein

G.S.,

Invasive fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Passive responders or transformed aggressors?. Arthritis and Rheumatism.

1996;

39

(11)

:

1781-90

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Xu

H.,

Edwards

J.,

Banerji

S.,

Prevo

R.,

Jackson

D.G.,

Athanasou

N.A.,

Distribution of lymphatic vessels in normal and arthritic human synovial tissues. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

2003;

62

(12)

:

1227-9

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Iwanaga

T.,

Shikichi

M.,

Kitamura

H.,

Yanase

H.,

Nozawa-Inoue

K.,

Morphology and functional roles of synoviocytes in the joint. Archives of Histology and Cytology.

2000;

63

(1)

:

17-31

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Jay

G.D.,

Torres

J.R.,

Warman

M.L.,

Laderer

M.C.,

Breuer

K.S.,

The role of lubricin in the mechanical behavior of synovial fluid. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

2007;

104

(15)

:

6194-9

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Takemura

S.,

Braun

A.,

Crowson

C.,

Kurtin

P.J.,

Cofield

R.H.,

O'Fallon

W.M.,

Lymphoid neogenesis in rheumatoid synovitis. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950).

2001;

167

(2)

:

1072-80

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Du

H.,

Zhang

X.,

Zeng

Y.,

Huang

X.,

Chen

H.,

Wang

S.,

A novel phytochemical, DIM, inhibits proliferation, migration, invasion and TNF-α induced inflammatory cytokine production of synovial fibroblasts from rheumatoid arthritis patients by targeting MAPK and AKT/mTOR signal pathway. Frontiers in Immunology.

2019;

10

:

1620

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Lafyatis

R.,

Remmers

E.F.,

Roberts

A.B.,

Yocum

D.E.,

Sporn

M.B.,

Wilder

R.L.,

Anchorage-independent growth of synoviocytes from arthritic and normal joints. Stimulation by exogenous platelet-derived growth factor and inhibition by transforming growth factor-beta and retinoids. The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

1989;

83

(4)

:

1267-76

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kawai

T.,

Akira

S.,

The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nature Immunology.

2010;

11

(5)

:

373-84

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Arleevskaya

M.I.,

Larionova

R.,

Brooks

W.H.,

Bettacchioli

E.,

Renaudineau

Y.,

Toll-like receptors, infections, and rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology.

2019;

58

(2)

:

172-181

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Zhu

L.J.,

Yang

T.C.,

Wu

Q.,

Yuan

L.P.,

Chen

Z.W.,

Luo

M.H.,

Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) 6 inhibition mitigates the pro-inflammatory roles and proliferation of rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Cytokine.

2017;

93

:

26-33

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Nasser

M.,

Hazem

N.M.,

Atwa

A.,

Baiomy

A.,

Evaluation of Toll-like Receptor 2 Gene Expression in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Correlation with the Disease Activity. Current Chemical Biology.

2019;

13

(2)

:

140-8

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Hu

F.,

Li

Y.,

Zheng

L.,

Shi

L.,

Liu

H.,

Zhang

X.,

Toll-like receptors expressed by synovial fibroblasts perpetuate Th1 and th17 cell responses in rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One.

2014;

9

(6)

:

e100266

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Qu

Z.,

Huang

X.N.,

Ahmadi

P.,

Andresevic

J.,

Planck

S.R.,

Hart

C.E.,

Expression of basic fibroblast growth factor in synovial tissue from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and degenerative joint disease. Laboratory Investigation.

1995;

73

(3)

:

339-46

.

PubMed Google Scholar -

Chikazu

D.,

Hakeda

Y.,

Ogata

N.,

Nemoto

K.,

Itabashi

A.,

Takato

T.,

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2 directly stimulates mature osteoclast function through activation of FGF receptor 1 and p42/p44 MAP kinase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry.

2000;

275

(40)

:

31444-50

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Tarhan

F.,

Vural

F.,

Kosova

B.,

Aksu

K.,

Cogulu

O.,

Keser

G.,

Telomerase activity in connective tissue diseases: elevated in rheumatoid arthritis, but markedly decreased in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology International.

2008;

28

(6)

:

579-83

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Tsumuki

H.,

Hasunuma

T.,

Kobata

T.,

Kato

T.,

Uchida

A.,

Nishioka

K.,

Basic FGF-induced activation of telomerase in rheumatoid synoviocytes. Rheumatology International.

2000;

19

(4)

:

123-8

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Bottini

A.,

Wu

D.J.,

Ai

R.,

Le Roux

M.,

Bartok

B.,

Bombardieri

M.,

PTPN14 phosphatase and YAP promote TGFβ signalling in rheumatoid synoviocytes. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

2019;

78

(5)

:

600-9

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Remmers

E.F.,

Sano

H.,

Lafyatis

R.,

Case

J.P.,

Kumkumian

G.K.,

Hla

T.,

Production of platelet derived growth factor B chain (PDGF-B/c-sis) mRNA and immunoreactive PDGF B-like polypeptide by rheumatoid synovium: coexpression with heparin binding acidic fibroblast growth factor-1. The Journal of Rheumatology.

1991;

18

(1)

:

7-13

.

PubMed Google Scholar -

Charbonneau

M.,

Lavoie

R.R.,

Lauzier

A.,

Harper

K.,

McDonald

P.P.,

Dubois

C.M.,

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor activation promotes the prodestructive invadosome-forming phenotype of synoviocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950).

2016;

196

(8)

:

3264-75

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Aupperle

K.,

Bennett

B.,

Han

Z.,

Boyle

D.,

Manning

A.,

Firestein

G.,

NF-κ B regulation by I κ B kinase-2 in rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950).

2001;

166

(4)

:

2705-11

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Karin

M.,

Yamamoto

Y.,

Wang

Q.M.,

The IKK NF-κ B system: a treasure trove for drug development. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery.

2004;

3

(1)

:

17-26

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Lawrence

T.,

The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology.

2009;

1

(6)

:

a001651

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Noort

A.R.,

Tak

P.P.,

Tas

S.W.,

Non-canonical NF-κB signaling in rheumatoid arthritis: Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde?. Arthritis Research {&}amp; Therapy.

2015;

17

(1)

:

1-10

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Wu

Z.M.,

Xiang

Y.R.,

Zhu

X.B.,

Shi

X.D.,

Chen

S.,

Wan

X.,

Icariin represses the inflammatory responses and survival of rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes by regulating the TRIB1/TLR2/NF-kB pathway. International Immunopharmacology.

2022;

110

:

108991

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Min

H.K.,

Won

J.Y.,

Kim

B.M.,

Lee

K.A.,

Lee

S.J.,

Lee

S.H.,

Interleukin (IL)-25 suppresses IL-22-induced osteoclastogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis via STAT3 and p38 MAPK/IκBα pathway. Arthritis Research & Therapy.

2020;

22

(1)

:

1-11

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Zhai

K.F.,

Duan

H.,

Luo

L.,

Cao

W.G.,

Han

F.K.,

Shan

L.L.,

Protective effects of paeonol on inflammatory response in IL-1β-induced human fibroblast-like synoviocytes and rheumatoid arthritis progression via modulating NF-κB pathway. Inflammopharmacology.

2017;

25

(5)

:

523-32

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Yang

L.,

Liu

R.,

Ouyang

S.,

Zou

M.,

Duan

Y.,

Li

L.,

Compounds DRG and DAG, Two Phenol Glycosides, Inhibit TNF-α-stimulated Inflammatory Response through Blocking NF-kB/AKT/JNK Signaling Pathways in MH7A Cells. Inflammation.

2021;

44

(5)

:

1762-70

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Burrage

P.S.,

Mix

K.S.,

Brinckerhoff

C.E.,

Matrix metalloproteinases: role in arthritis. Frontiers in Bioscience.

2006;

11

(1)

:

529-43

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Ni

S.,

Li

C.,

Xu

N.,

Liu

X.,

Wang

W.,

Chen

W.,

Follistatin-like protein 1 induction of matrix metalloproteinase 1, 3 and 13 gene expression in rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes requires MAPK, JAK/STAT3 and NF-κB pathways. Journal of Cellular Physiology.

2018;

234

(1)

:

454-63

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Miller

M.C.,

Manning

H.B.,

Jain

A.,

Troeberg

L.,

Dudhia

J.,

Essex

D.,

Membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase is a crucial promoter of synovial invasion in human rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism.

2009;

60

(3)

:

686-97

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Hegemann

N.,

Wondimu

A.,

Ullrich

K.,

Schmidt

M.F.,

Synovial MMP-3 and TIMP-1 levels and their correlation with cytokine expression in canine rheumatoid arthritis. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology.

2003;

91

(3-4)

:

199-204

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Ma

J.D.,

Jing

J.,

Wang

J.W.,

Yan

T.,

Li

Q.H.,

Mo

Y.Q.,

A novel function of artesunate on inhibiting migration and invasion of fibroblast-like synoviocytes from rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Research & Therapy.

2019;

21

(1)

:

153

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Hou

W.S.,

Li

Z.,

Gordon

R.E.,

Chan

K.,

Klein

M.J.,

Levy

R.,

Cathepsin k is a critical protease in synovial fibroblast-mediated collagen degradation. American Journal of Pathology.

2001;

159

(6)

:

2167-77

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kurowska

W.,

Slowinska

I.,

Krogulec

Z.,

Syrowka

P.,

Maslinski

W.,

Antibodies to Citrullinated Proteins (ACPA) Associate with Markers of Osteoclast Activation and Bone Destruction in the Bone Marrow of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Journal of Clinical Medicine.

2021;

10

(8)

:

1778

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Salminen-Mankonen

H.J.,

Morko

J.,

Vuorio

E.,

Role of cathepsin K in normal joints and in the development of arthritis. Current Drug Targets.

2007;

8

(2)

:

315-23

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Wang

H.,

Wang

Z.,

Wang

L.,

Sun

L.,

Liu

W.,

Li

Q.,

IL-6 promotes collagen-induced arthritis by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome through the cathepsin B/S100A9-mediated pathway. International Immunopharmacology.

2020;

88

:

106985

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Hashimoto

Y.,

Kakegawa

H.,

Narita

Y.,

Hachiya

Y.,

Hayakawa

T.,

Kos

J.,

Significance of cathepsin B accumulation in synovial fluid of rheumatoid arthritis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications.

2001;

283

(2)

:

334-9

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Tong

B.,

Wan

B.,

Wei

Z.,

Wang

T.,

Zhao

P.,

Dou

Y.,

Role of cathepsin B in regulating migration and invasion of fibroblast-like synoviocytes into inflamed tissue from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical and Experimental Immunology.

2014;

177

(3)

:

586-97

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Walsh

D.A.,

Catravas

J.,

Wharton

J.,

Angiotensin converting enzyme in human synovium: increased stromal [(125)I]351A binding in rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

2000;

59

(2)

:

125-31

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Guo

X.,

Chen

G.,

Hypoxia-inducible factor is critical for pathogenesis and regulation of immune cell functions in rheumatoid arthritis. Frontiers in Immunology.

2020;

11

:

1668

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Hu

Y.,

Zhang

T.,

Chen

J.,

Cheng

W.,

Chen

J.,

Zheng

Z.,

Downregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α by RNA interference alleviates the development of collagen-induced arthritis in rats. Molecular Therapy. Nucleic Acids.

2020;

19

:

1330-42

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Hot

A.,

Zrioual

S.,

Lenief

V.,

Miossec

P.,

IL-17 and tumour necrosis factor α combination induces a HIF-1α-dependent invasive phenotype in synoviocytes. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

2012;

71

(8)

:

1393-401

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Cha

H.S.,

Ahn

K.S.,

Jeon

C.H.,

Kim

J.,

Song

Y.W.,

Koh

E.M.,

Influence of hypoxia on the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1, -3 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 in rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology.

2003;

21

(5)

:

593-8

.

PubMed Google Scholar -

Ahn

J.K.,

Koh

E.M.,

Cha

H.S.,

Lee

Y.S.,

Kim

J.,

Bae

E.K.,

Role of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in hypoxia-induced expressions of IL-8, MMP-1 and MMP-3 in rheumatoid fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Rheumatology (Oxford, England).

2008;

47

(6)

:

834-9

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Hu

F.,

Liu

H.,

Xu

L.,

Li

Y.,

Liu

X.,

Shi

L.,

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α perpetuates synovial fibroblast interactions with T cells and B cells in rheumatoid arthritis. European Journal of Immunology.

2016;

46

(3)

:

742-51

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Szekanecz

Z.,

Koch

A.E.,

Vascular involvement in rheumatic diseases: `vascular rheumatology'. Arthritis Research & Therapy.

2008;

10

(5)

:

224

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kernder

A.,

Mucke

J.,

Tang-Chieu

L.,

Lowin

T.,

Cla\ssen

T.,

Sander

O.,

AB0125 CXCL17 in rheumatoid arthritis: interferone-gamma inducible expression and inhibition of angiogenesis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

2019;

78

:

1523

.

-

Achudhan

D.,

Liu

S.C.,

Lin

Y.Y.,

Lee

H.P.,

Wang

S.W.,

Huang

W.C.,

Antcin K inhibits VEGF-dependent angiogenesis in human rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Journal of Food Biochemistry.

2022;

46

(1)

:

e14022

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kim

K.W.,

Kim

H.R.,

Kim

B.M.,

Cho

M.L.,

Lee

S.H.,

Th17 cytokines regulate osteoclastogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. American Journal of Pathology.

2015;

185

(11)

:

3011-24

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Danks

L.,

Komatsu

N.,

Guerrini

M.M.,

Sawa

S.,

Armaka

M.,

Kollias

G.,

RANKL expressed on synovial fibroblasts is primarily responsible for bone erosions during joint inflammation. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

2016;

75

(6)

:

1187-95

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Park

J.H.,

Lee

N.K.,

Lee

S.Y.,

Current understanding of RANK signaling in osteoclast differentiation and maturation. Molecules and Cells.

2017;

40

(10)

:

706-13

.

PubMed Google Scholar -

Kim

K.W.,

Kim

H.R.,

Park

J.Y.,

Park

J.S.,

Oh

H.J.,

Woo

Y.J.,

Interleukin-22 promotes osteoclastogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis through induction of RANKL in human synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis and Rheumatism.

2012;

64

(4)

:

1015-23

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Feng

X.,

Shi

Y.,

Xu

L.,

Peng

Q.,

Wang

F.,

Wang

X.,

Modulation of IL-6 induced RANKL expression in arthritic synovium by a transcription factor SOX5. Scientific Reports.

2016;

6

(1)

:

32001

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kim

K.W.,

Kim

B.M.,

Moon

H.W.,

Lee

S.H.,

Kim

H.R.,

Role of C-reactive protein in osteoclastogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Research & Therapy.

2015;

17

(1)

:

41

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Abdel-Maged

A.E.,

Gad

A.M.,

Abdel-Aziz

A.K.,

Aboulwafa

M.M.,

Azab

S.S.,

Comparative study of anti-VEGF Ranibizumab and Interleukin-6 receptor antagonist Tocilizumab in Adjuvant-induced Arthritis. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology.

2018;

356

:

65-75

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Wang

F.,

Luo

A.,

Xuan

W.,

Qi

L.,

Wu

Q.,

Gan

K.,

The bone marrow edema links to an osteoclastic environment and precedes synovitis during the development of collagen induced arthritis. Frontiers in Immunology.

2019;

10

:

884

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kim

H.R.,

Kim

K.W.,

Kim

B.M.,

Cho

M.L.,

Lee

S.H.,

The effect of vascular endothelial growth factor on osteoclastogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One.

2015;

10

(4)

:

e0124909

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Wakisaka

S.,

Suzuki

N.,

Takeba

Y.,

Shimoyama

Y.,

Nagafuchi

H.,

Takeno

M.,

Modulation by proinflammatory cytokines of Fas/Fas ligand-mediated apoptotic cell death of synovial cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Clinical and Experimental Immunology.

1998;

114

(1)

:

119-28

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Annibaldi

A.,

Walczak

H.,

Death Receptors and Their Ligands in Inflammatory Disease and Cancer. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology.

2020;

12

(9)

:

a036384

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Perlman

H.,

Pagliari

L.J.,

Liu

H.,

Koch

A.E.,

Haines

G.K.,

Pope

R.M.,

Rheumatoid arthritis synovial macrophages express the Fas-associated death domain-like interleukin-1β-converting enzyme-inhibitory protein and are refractory to Fas-mediated apoptosis. Arthritis and Rheumatism.

2001;

44

(1)

:

21-30

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Schedel

J.,

Gay

R.E.,

Kuenzler

P.,

Seemayer

C.,

Simmen

B.,

Michel

B.A.,

FLICE-inhibitory protein expression in synovial fibroblasts and at sites of cartilage and bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism.

2002;

46

(6)

:

1512-8

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Perlman

H.,

Liu

H.,

Georganas

C.,

Koch

A.E.,

Shamiyeh

E.,

Haines

G.K.,

Differential expression pattern of the antiapoptotic proteins, Bcl-2 and FLIP, in experimental arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism.

2001;

44

(12)

:

2899-908

.