Abstract

Over recent years, nanotechnology has been used in a wide variety of applications, including different fields of medical diagnosis and treatment. Migraine is a neurobiological disorder that is associated with severe headaches and other autonomic and neurological symptoms. The interaction between nanomaterials and immune system components is among the areas of interest in treatment measures. This review summarizes advances made in the understanding of the genes and genetic variations associated with migraines and discusses the potential applications of nanomedicine for treatment and prevention of the disorder.

Introduction

Headaches are a common chronic disease symptom. Most people, if not all, will suffer from headaches at some point in their lives. The incidence of symptoms with a neurological basis is a global problem, and India is no exception. Tissues and structures near the skull are the sources of the pain. Primary, secondary, and cranial neuralgia are the most common types of headaches. Primary headache disorders fall into four categories: migraine, tension-type headaches, trigeminal autonomic encephalalgia, and others. Today, migraine is the commonest form of headache worldwide1. Over 20% of the population suffers from migraine, a degenerative disorder that is costly to treat and leads to lost productivity2. A major drawback of modern diagnostic procedures is that they are largely clinical, and symptoms can overlap with those of other neurological disorders, which complicates diagnosis and creates comorbidity issues. It is believed that migraines are triggered by dysfunctional afferent regulation and control in the brain, with a strong focus on the skull3. Migraines are headaches that can result in unilateral throbbing, nausea, vomiting, phonophobia, and photophobia. As a result, migraine subtypes are distinguished by the presence or absence of aura. Most migraineurs suffer from migraines without aura, whereas migraines with aura affect a smaller percentage of the population. There is a significant impact on the nervous system when migraines are present.

One of the most important factors in the pathogenesis of migraines is their hereditary nature; they are associated with a significant genetic component, with intricate complexities that encompass different subtypes. It has been suggested that single-gene migraines are uncommon variants of migraine4, originating from autosomal dominant polymorphisms in genes that encode signaling pathways. It has been observed in clinical practice that migraine patients often have a first-degree relative who also has the condition. It was documented that children may inherit a propensity for migraines from their parents, and various studies have found associated family histories5. It remains a challenge to determine which genes contribute to common migraine and how they interact with the environment. It is difficult to determine how genes interact with environmental factors in common migraine because of the complex nature of the disorder. A review of the research that has been conducted in recent years is presented in this article. It summarizes advancements in the understanding and knowledge of the genes and genetic variations associated with migraine and the potential applications of nanomedicine in alleviating the condition.

Genetic Epidemiology

The significant roles played by genetic and environmental factors have been investigated in twin-pair studies using the classical method (Table 1). A Danish study found that twin pairs are significantly more prevalent among monogenetically matched pairs than dizygotic pairs6. Researchers have explored the family inheritance pattern for migraines in some studies, with contradictory results7. The exact cause of migraine without aura is unknown, but research done on twins and population epidemiological surveys suggests that it is a complex condition caused by hereditary and environmental factors8. Mutations in the methyltetrahydrofolate reductase gene may cause migraine with aura9. The cause is unclear, but the disease has been well-established. In rare hereditary instances, such as autosomal-dominant retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukodystrophy, the aura may be linked to structural protein malfunction and a menial patent10. According to this view, migraine discomfort can be explained by shared genetics versus a pathophysiology relationship.

| Genes** | Chromosomal region | Migraine type | Roles | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGR2 | X chromosome | Familial type migraine | Acts as mediated gatekeeper function for transfer and stop signals in mitochondria | 11 |

| KCNK18 | 10q25 | With aura | Encodes two-pore domain potassium(K2P) channel TRESK protein, contains premature stop codons in both painful and painless diabetic peripheral neuropathy | 12 |

| CACNA1A (FHM1) | 19p13 | Autosomal dominant migraine with aura | Mutations in the ion transportation genes, an alpha-1A subunit of CaV2.1 neuronal channels, control neurotransmitter release | 13 |

| ATP1A2 (FHM2) | 1q23 | Autosomal dominant | α2 isoform of the catalytic subunit of Na+/K+- ATPase, and its dysfunction leads to an augmentation of synaptic potassium and glutamate. | 14 |

| SCN1A (FHM3) | 2q24 | Autosomal dominant | Encodes the α1 subunit of voltage-gated sodium channels (NAV1.1), exhibits deregulation of excitatory-inhibitory balance in the brain, and well known in epilepsy causes poor prognosis in Dravet syndrome | 15 |

| ESR1 | 6q25.1-q25.2 | Autosomal dominant | Encodes estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) which controls ligand-dependent transcription factor and relates to neurological diseases such as Alzheimer's diseases | 16 |

| TNFα gene | 6p21.3 | Autosomal dominant | Proinflammatory cytokine | 17 |

| Endothelin receptor type A gene | 4q31.22 | Autosomal dominant | Encodes a guanine-nucleotide-binding protein-coding gene associated with ETA receptor and endothelin-1 | 18 |

| LRP1 | 12q13 | Migraine without aura | Encodes for neuronal signal transmission, mainly in brain and blood vessels, play a significant role in neuronal glutamate signaling | 19 |

| MEF2D | 1q22 | All migraine; migraine without aura | Encodes the protein functions from inflammation–induced toxicity and myocyte-specific enhancer factor 2D transcription factor | 20 |

| ASTN2 | 9q33 | All migraine | Encodes proteins involved in neuronal migration, such as astrotactin 2 | 21 |

| FHL5 | 6q16 | Migraine without aura | Encodes activator of cAMP-responsive element modulator and activation of a transcriptional function, and the gene responsible for stroke and extracranial cervical artery dissection | 22 |

| TRPM8 | 2q37 | Migraine without aura | Encodes a non-selective cation channel expressed in primary afferent neurons and relates to the primary cold thermos-sensor TRPM8 receptors and alterations in the transcriptional regulation | 23 |

| MMP16 | 8q21 | Migraine without aura | Encodes protein related to the metalloproteinase family | 24 |

| AJAP1 | 1p36 | All migraine | Encodes beta-catenin binding activity involves in negative regulation in cell-matrix adhesion, and adherens junctions associated protein 1 | 25 |

| TSPAN2 | 1p13 | All migraine | Member of the tetraspanin superfamily and has a potential role in oligodendrogenesis and is also associated with retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukoencephalopathy | 26 |

| TGFBR2 | 3p24 | All migraine | Encodes in vascular development negative a regulator signaling and acts as a coreceptor to initiate signaling | 27 |

| PRDM16 | 1p36 | All migraine | Zinc-finger transcription factor, and alter gene slicing in introns, regulate relevant thermogenic gens in brown adipose tissue, involves in oxidative stress and neurogenesis | 28 |

| PHACTR1 | 6p24 | Migraine without aura | Identified as a distal regulator of endothelin-1, regulates vascular function, and is associated with many diseases, such as cervical artery dissection and fibromuscular dysplasia. | 29 |

| COL4A1/ COL4A2 | 13q34 | Migraine with aura, and retinal defects | Responsible for autosomal dominant cerebral angiopathy and congenital porencephaly, mostly among the triple helix of the missense glycine mutations | 30 |

| CALCA | 11p15 | All Migraine | Encodes mainly at the transcriptional level and regulated through the targeting unmethylated CpG island and the demethylation of internal regions of the gene; it's a potential therapeutic targeting migraine using glial cells using paracrine regulatory mechanism. | 31 |

| MTHFR | 1p36.3 | All types of Migraine | It is a key enzyme in the folate cycle and plays a major role in hyperhomocysteine accompanied by spontaneous trigeminal cell firing and metabolism and acts as a catalyzing and alterations in enzyme activity | 32 |

| SLC6A4 | 17q11.2 | All types of Migraine | Encodes membrane protein that carries neurotransmitter serotonin from synaptic spaces into presynaptic neurons in a sodium-dependent manner | 33 |

| STX1A | 7q11 | Migraine with Aura | Encodes in the regulation of neurotransmitters, and It is a single nucleotide polymorphism located in the neuronal synaptic plasma membrane that plays a major role in the neurodevelopment disorders | 34 |

| GRIA1 & GRIA3 | Xq25 | Migraine without Aura | Encodes the AMPA-type glutamate receptor subunits, and it involves in trigeminovascular activation, central sensitization, and cortical spreading depression | 35 |

Migraine Aura

An aura is a sensory, motor, or visual disturbance that occurs as a result of a localized neurological disruption36, 37. Approximately 30% of patients with this symptom experience cognitive dysfunction38. Like the human version of cortical spreading depression (CSD) in rabbits, the aura is often referred to as the neurological disturbance appearing during the migraine. The aura's expression has been characterized as beginning in the visual field's core and passing through the striate cortex, which affects vision. The rabbit's spreading depression is very similar to this process. Furthermore, patients' circulatory tests have revealed that localized hyperemia usually develops before the spreading of oligemia, which is consistent with what one would expect to occur during depression spread39. In patients with oligemia, hypercapnia has an adverse effect on the cerebrovascular system, whereas autoregulation remains intact. A repetition of this cycle occurs when experimental spreading depression is induced. Several studies have indicated that there is a correlation between migraine and the menopause, in which migraines in women can last far into the menopause40. Research in humans, particularly recent research suggesting that ketamine—which is known to inhibit CSD in animals—can be used to treat patients with protracted aura, supports the hypothesis that human aura is similar to CSD in animals. Arguments abound over whether aura is unpleasant and enables the rest of the assault. In humans, evidence of migraine aura without headache—a well-known condition—indicates that it is not severe41.

Familial Hemiplegic Migraine (FHM)

FHM is an autosomal dominant condition that passes from generation to generation in a monogenic manner. Persistent headaches in FHM sufferers are typically triggered by eating certain foods, experiencing psychological distress, or even sustaining a slight head injury. Such headaches cause severe throbbing pain in one part of the head and have no definite time frame for how long they will last. Certain types of migraine, including FHM, can be preceded by a sequence of neurological problems known as an aura42. An aura is most commonly characterized by temporary abnormalities such as peripheral vision, zigzag lines, strobe lights, and double vision. When FHM affects one side of the body, auras can also be accompanied by momentary paralysis or fatigue. The migraine attacks can be very severe for those with this condition, with reports of fever, convulsions, difficulty speaking, sleepiness, and disorientation. There is a possibility of prolonged weakness, unconsciousness, and even death. The majority of people with FHM recover fully between attacks; however, neurological effects such as Alzheimer's disease can occur, and symptoms such as difficulty concentrating may last for several months. It is estimated that about 20% of those affected develop nystagmus (rapid, involuntary eye movements) and mild but persistent difficulty coordinating movements (ataxia), which is likely to worsen over time43. There is still no information available about how common FHM is around the globe. However, the condition is estimated to affect one in every million people in many countries. It can affect multiple members of a family, and people without a family history of the disease. As with other forms of migraine, FHM is inherited autosomally44. As it has a dominant mode of inheritance, only one copy of the mutated gene is sufficient to cause the disorder; sufferers have typically inherited from one parent only. Meanwhile, some individuals who have inherited a changed gene experience no symptoms of FHM.

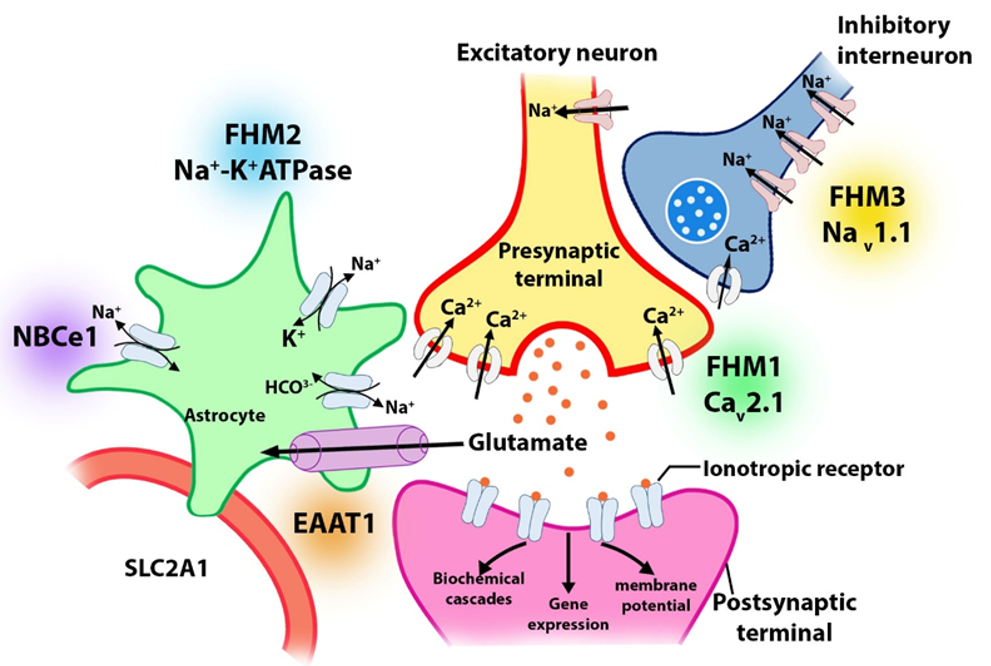

There are genetic differences between FHM and sporadic hemiplegic migraine (SHM). There are four genes related to hemiplegic migraine (HM) identified so far: 19p13 (FHM1) of CACNA1A, 1q23 (FHM2) of ATP1A2, 2q24 (FHM3) on SCN1A, and 16p11.2 of PRRT2 (fig. 1). Further, two additional loci at 1q31 and 14q32 have been identified in FHM families, although the specific abnormalities are not yet known. There have been many reported cases of FHM linked to chromosome 19p1345. Phylogenetic analysis showed that FHM families with and without such changes on chromosome 19 show few clinical differences. Although almost half of the 19-linked families were affected, none of the unlinked families was affected. Therefore, the clinical phenotype does not appear to be linked to any known mutations associated with cerebellar ataxia46.

CACNA1A is the gene that encodes a Cav2.1 type of calcium-gated channel. It provides the biological basis for the link with chromosome 19. Nearly half of all known families of migraineurs have this mutation, known as FHM1. An effect of the alteration is a potential increase in glutamate release. FHM has been associated with mitochondrial DNA mutations of the ATP1A2 gene in approximately 20% of cases47. Some patients with FHM2 suffer from epilepsy. In the mutated gene, an electrochemical gradient for Na+ is lowered because there is a mutation encoding a Na+/K+ ATPase, which causes a reduction or inactivation of astrocyte glutamate transporters, resulting in the accumulation of synaptic glutamate48. A mutation in SCN1A (Q1489K) causes FHM3. When membranes depolarize, this alteration disrupts an amino acid critical for maintaining the channel's opening/closing timing. This causes the channel to quickly shut after an action potential, allowing sodium to enter the membrane at a sustained rate.

5-HT Migraine and Serotonin Receptor

Activation of 5-HT1F, a serotonin receptor, lowers the threshold for activity and neuronal firing in the trigeminal nucleus in response to dural stimulation, without changing cranial vascular function. Triptans and other 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists have also been shown to activate 5-HT1F receptors. As an example of a highly effective medication administered intravenously, Naratriptan is a suitable choice49; adenylate cyclase inhibition, 5HT1B/T1D receptor activation, inhibition of blood pressure vessel contraction, and inhibition of 5HT1B receptor activity make it an ideal candidate for migraine treatment. An acute antimigraine medication, known as COL-144 or Lasmiditan, has also proved effective in a randomized controlled trial50, 51. Researchers have found that such compounds can be used to effectively treat acute migraines without adversely affecting vascular pathways52.

Effects of the Trigeminocervical Complex on Glutamatergic Transmission

In vivo studies have reported that NMDA receptor channel antagonists inhibit nociceptive trigeminovascular transmission. 2,3-Dioxo-6-nitro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro benzoquinoxaline-7-sulfonamide (NBQX) and 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) interactions were significantly suppressed. Glutamate receptors (GluRs), which include ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs), are targeted by compounds such as N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), amino-3-hydroxy-5 methylisoxazole-4-propionate (AMPA), and kainate, which are potential antimigraine drug candidates53. Following stimulation of components implicated in nociceptive pathways, expression of the Fos protein was suppressed in neurons with trigeminovascular inputs. CNQX was also observed to reduce nociceptive trigeminovascular inputs when administered directly to the trigeminocervical complex. L-(+)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid decreased group III mGluR receptor Fos protein expression in an invasive study focusing on trigeminovascular nociceptive perception54. ADX10059 is also useful for the treatment of acute migraines since it is a group I mGluR5 modulator. In contrast, the "high affinity" KA1 and KA2 subunits combine to create distinct homomeric assemblies, which result in functioning receptors. It has recently been discovered that the specific agonist iodowillardiine inhibits neurogenic dural vasodilation by activating the kainate receptors on the IGF-R5 channel, thereby preventing calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) release from trigeminal afferents. A study has demonstrated that kainate receptors are key players in the physiology of trigeminal ganglion (TG) neurons and primary afferents55. Furthermore, inhibiting kainate receptors on iGluR5 decreased pain in severe migraine in two 2-fold randomized placebo-controlled trials. A separate study has shown that infusion with the AMPA/iGluR5 antagonist decahydroisoquinoline significantly reduced migraine headaches and eased the accompanying symptoms in two-thirds of migraineurs. All these findings provide a solid foundation for pursuing glutamate receptors, with caution required to avoid unwanted side effects.

CGRP (Calcitonin Gene-related Peptide

Inflammatory neuropeptides such as CGRP are found in the meninges, trigeminal ganglia, trigeminocervical complex, brainstem nuclei, thalamus, and cortex, which are all associated with migraine pathogenesis. The triggering of peripheral trigeminocervical receptors occurs as a result of neurogenic inflammation in migraine originating from the brainstem or cortex. There is a subsequent release of neuroinflammatory peptides such as CGRP56. It is believed that the CGRP pathway is responsible for neurogenic vasodilation, resulting in the extravasation of plasma proteins and mast cells, both of which contribute to inflammation. A neurogenic inflammation within the peripheral nervous system causes sensitization of the nerve endings, which spreads through the trigeminal axon, the brainstem, the thalamus, and eventually into the cortex. According to an in vivo study, CGRP was produced after central nervous system (CNS) activation, just as in migraines57. Triflatans prevent animals from producing CGRP. The majority of nociceptive TG neurons produce unmyelinated C-fibers, with about half releasing CGRP neuropeptide. In contrast, CGRP receptors are found in the majority of neurons in the dura's vascular system, as well as in the smooth muscle tissue that lines the dura's lumen. A majority of TG neurons generate unmyelinated C-fibers that produce CGRP neuropeptide. As with CGRP receptors, they are found in the majority of neurons in the dura's vasculature and the myelinated A-fibers—another type of TG fiber. CGRP is found in two isoforms: while CGRP is mainly found in the CNS and peripheral nerves of the somatosensory system, beta-isoforms are mainly found in the enteric nervous system and motor neurons58. Human migraine sufferers have delayed onset of headaches when CGRP is infused into their bodies. Research has found that the decrease in CGRP levels in the blood is reduced in response to triptan medications, which are specific to the recovery of migraine. In several clinical studies looking at the CGRP pathway for migraine relief, antagonists of the CGRP receptor and antibodies targeting CGRP have shown promise. In migraine treatment, CGRP antagonists were shown to be helpful. A CGRP receptor antagonist has been developed from this research, which may prevent vasodilation caused by neurogenic factors in the meninges. The evidence suggests that activity of the TG limits vasoconstriction. Due to its ability to inhibit CGRP release from the TG, sumatriptan injections led to decreased levels of blood CGRP, which decreased headache severity59. Another study concluded that greater salivary CGRP levels are associated with better therapeutic response to rizatriptan, possibly helping select patients for specialized migraine treatment. There are currently phase III studies being conducted with Olcegepant and Telcagepant, two CGRP-receptor antagonists. While triptans have the potential to cause negative vasoconstrictive effects, this new class of drugs does not.

Cytokines

Recent research suggests that CGRP stimulates CGRP receptors on T-cells, causing them to secrete cytokine50. Trigeminal nerve fiber sensitization is regulated by cytokines, which play a role in inflammation and pain tolerance. Cytokine-induced headaches have been demonstrated in a number of studies. In studies, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) injections were found to cause headaches, whereas anti-TNF antibodies alleviated the pain in humans. During migraine symptoms, both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines are raised within the circulation51. As migraine discomfort starts, TNF levels rise, and they gradually fall after the attack has passed. IL-1, a cytokine associated with inflammation, is also elevated following the appearance of a headache. Hyperalgesia can also be caused by TNF stimulating the production of IL-1. There is evidence that the amount of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 increases after the beginning of a headache, suggesting that it may play a role in insensibility. One study has investigated whether IL-10 could suppress the release of TNF, an antinociceptive60. There have been mixed results regarding migraineurs' cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels. Studies showed that migraine patients and episodic tension-type headache (TTH) sufferers had higher levels of IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and transforming growth factor-1 (TGF-1) than their pain-free counterparts61. Cytokines are assumed to be associated with pain or to cause pain to occur if their concentrations in the CSF are imbalanced. Neither migraine nor episodic TTH is associated with cytokine; there was no difference in cytokine levels between the two conditions.

Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)

TRAF proteins typically have a secondary structure that includes a homologous proline-rich region at the C-terminal called the TRAF domain and an array of zinc fingers. The N-terminal region of all TRAF members, except TRAF1, has a RING domain62. It is the TRAF domain that mediates TRAF protein oligomerization, as well as their interaction with upstream receptors or adapters and downstream effector proteins. Inflammation and pain are both activated by TNF, a pro-inflammatory cytokine. Symptoms often develop in people who have newly developed daily persistent headaches (NDPH) after infection63. Cytokine-like TNF can reactivate and prolong inflammation in CNS even after the infection has cleared. A study suggests that TNFs may contribute to headache genesis. In refractory persistent daily headaches, TNF levels in the CSF may increase64. NDPH and high TNF levels commonly result in patients who are refractory to a wide range of drugs. The presence of TNF contributes to a variety of diseases, such as sinusitis, rhinitis, and headaches. Such disorders may, therefore, be helped with drugs that modify TNF.

Role of Neuropeptides (NP) in the

In response to electrical stimulation of the TG, CGRP and SP are released locally. A higher level of CGRP in the jugular vein may be associated with greater cerebral blood flow and pain caused by stimulation of the superior sagittal sinus65. There is evidence that CGRP levels are elevated in severe migraines. According to several studies, the TGVS may play an important part in preventing chronic paroxysmal hemicrania and cluster headaches. In the same way as natural compounds associated with migraine, sumatriptan can block CGRP increases via this mechanism. Non-peptidic CGRP receptor antagonists are highly specific, and the clinical success of at least four such compounds in acute migraine treatment firmly establishes the concept as a novel approach to treating the condition66. There are probably no biomarkers for migraine.

CaCNA1A is a member of the gene family that encodes calcium channels. These ion channels, which transport positively charged calcium atoms across membranes, assist cells in generating and transmitting electrical signals. Cell membranes transmit and generate electrical signals with the help of calcium ions. The calcium ions regulate various cellular functions, including intercellular communication, muscle contractions, and gene expression. Calcium channel alpha-1 gene CaCNA1A codes for the channel's pore-forming unit through which calcium ions pass67. The CaV2.1 channel plays a crucial role in nerve cell communication. Signals between neurons are transmitted by neurotransmitters, the release of which is controlled by these nerve channels. CaV2.1 channels are also believed to play a crucial role in neuron survival as well as allowing these cells to adapt and change over time. A migraine headache that is accompanied by neurological symptoms, such as an aura, causes this condition. FHM1 is caused by a single amino acid change in CaV2.1, which affects the functioning of this channel (Figure 1). Methionine replaces the amino acid threonine at protein position 666 of CaCNA1A in many affected families. By increasing calcium entry into the cells, CACNA1A gene mutations have been confirmed to cause SHM in nine patients. Despite the similarity of its signs and symptoms, SHMs usually occur in people without a family history of the condition. CACNA1A gene mutations are frequently connected to SHM, which causes ataxia and nystagmus, as well as migraine headaches and auras. The CaV2.1 channel is more active when its amino acid sequence is altered, resulting in abnormal neuronal communication; auras and headaches associated with hemiplegic migraines are common in this condition68, 69. According to some studies, migraine or migraine symptoms—or at least their neurological counterparts, such as the aura—are myopathies that are associated with particular mutations. In a knock-in mouse model, researchers have found that equivalent human mutations lead to a lower threshold for CSD. This is the first time that channel disruption has been linked to aura development. Compared to wild-type mice, these knock-in mice exhibit reduced second-order neuronal activity, as well as a significantly higher level of Fos protein expression in certain thalamic nuclei. This mutation may have a significant pathological impact on the thalamocortical system. The KCNK18/TRESK gene was found to be associated with migraine diagnosis, suggesting it is a causative mutation32. The calcium-dependent phosphatase, calcineurin, regulates cellular excitability via the TRESK gene, which belongs to a family of potassium channels with two pore-forming domains. In migraine families, the most commonly altered genes are those involved in oxytocin receptor signaling, serotonin receptor signaling, thyrotropin-releasing hormone signaling, Alzheimer's disease amyloid secretase, GQ alpha, and GQ beta pathways, as well as the ATXN1, FAM153B, and CACNA1B genes70. People without a family history of the disorder are vulnerable to SHM, which has similar symptoms.

The environment can also affect migraine susceptibility in addition to genetic factors. Studying monozygotic twins has revealed the following: The majority of MO (migraine without aura) cases are inherited, while the remainder are influenced by the environment. On average, a migraine sufferer's frequency increases threefold during menstruation and pregnancy, and a link between decreases in migraine frequency and hormonal changes during menopause has been identified. Other migraine triggers include lack of sleep, eating habits, and stress71. Therapies utilizing hormones can alter a nuclear pathway that affects the trigeminal nociceptive pathway. Molecular receptors can modulate epigenetic programming, resulting in chromatin remodeling and changes in gene expression. Studies in rats have shown that hormonal treatments affect epigenetic programming on certain genes72. Estrogenic receptor β regulates Glut4 transport by limiting DNA methylation at its promoter. Activation of estrogenic receptor β reduces DNA methylation at the promoter and increases expression of SLC1a3 and Eaat173. These changes affect inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmission. CSD depression, epilepsy, and stroke are more likely to occur in mice carrying an FHM mutation. Neuronal plasticity and neuroprotection are likely to be altered by epigenetics in CSD. MTHFR polymorphisms are highly sensitive to epigenetic programming associated with migraines, which is normally modulated by stress. MTHFR is among several genes related to migraine pathophysiology that have been linked to epigenetic processes that generate the methyl donor for DNA methylation74. Epigenetics and migraine are associated with several genes, but further research is needed to understand the details of how the environment affects migraine risk.

Role of Mitochondria in Migraine

The mitochondrial genome does not undergo recombination. Different mitochondrial diseases can all be linked to a specific variant. The mitochondrial genome of migraine sufferers is subject to various investigations for numerous reasons. Through the electron transport chain, the mitochondrion primarily operates as a source of ATP75. Mitochondrial dysfunction decreases ATP production, resulting in oxidative stress. Detrimental effects of mtDNA variations are likely to be experienced by people with migraine issues. For neurons to function normally, mitochondria are essential for calcium ion homeostasis76. Migraines are often a comorbidity of many mitochondrial disorders, according to many recent studies. Mitochondrial dysfunction among migraine patients in certain brain regions has been reported. This has been linked to other neurological conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis77. In the HUNT study—a large cohort survey—the mitochondrial migraine participants did not share a common genetic variation related to migraine. Several aspects of the study require further investigation. Although distant maternal relatives may have the same mtDNA, they may not necessarily share other genetic risk factors, such as variations in nuclear DNA. There is no known method of accounting for close maternal relatedness when performing mitochondrial association studies78. Heteroplasmy has been observed to exacerbate many mitochondrial diseases. Further study is needed in migraineurs with mitochondrial dysfunction. More research is needed to understand the impact of rare variations, mutations of mitochondrial encoding, and environmental factors.

Role of the X Chromosome

Migraines have been shown to have a genetic component, and there is also evidence that gender is an important factor. Migraines are more prevalent among women, as evidenced by numerous population studies that found a 3:1 female-to-male incidence ratio79. It is common in both MO and MA to have an unequal gender distribution among migraine sufferers. Migraines are inherited in a dominant manner, suggesting hormonal effects or a link to the X chromosome. In several studies examining how migraine susceptibility is genetically associated with the X chromosome, results from linkage analyses demonstrate that the X chromosome is associated with migraine susceptibility80. Haplotype analysis enabled further refinement by indicating that migraine susceptibility loci are located on Xq24-28. A study by Maher et al. reported that migraine susceptibility loci are also present on Xq27 and Xq12, using a genetically isolated Norfolk Island population81. Before this study, no genes or genetic variants associated with migraine risk had been identified within these regions. Other studies on the X chromosome of a migraine-suffering family found a link to Xp22. The synapsin I gene (SYN1) on the X chromosome has been linked to migraine via case-control studies82. In a study that genotyped 119 SNPs in molecular machinery genes and neurotransmission genes in 188 migraine patients and 286 healthy controls, the researchers found that the rs5906437 GC genotype protects against migraine, while the rs5906435 G allele increases migraine susceptibility in women, but not in men80. A larger sample size may be necessary to confirm whether this is a gender-specific effect.

Role of Migraine in Cerebrovascular Disorder

Migraine and ischaemic stroke are positively associated. Vessel wall dysfunction results in vasoreactivity changes and cerebral blood flow. Embolization of the heart occurs when blood is shunted through the extracardiac system. Shunts in the heart or extracardiac place are paradoxical to embolization83. Patients without aura had significantly fewer microinfarcts in the posterior circulation territory than migraine patients with aura. As a result of CSDs, cerebral perfusion pressure and cerebral blood flow are reduced. MRIs of posterior circulation territories of migraine patients without aura revealed fewer microinfarcts than those of migraine patients with aura84. By allowing occluding particles to accumulate, CSD may decrease cerebral perfusion pressure and blood flow, thereby contributing to cerebral ischemia. There is a change in vasoreactivity and cerebral blood flow due to vessel wall dysfunction. In contrast, procoagulant factor release causes endothelium-dependent relaxation to be reduced and oxidative stress and inflammation of vessels to be increased. Women with active migraine aura are more likely to suffer an ischaemic stroke caused by migraines85. Despite the differences in pain intensity and direction, migraines may be associated with major cardiovascular events.

Pathophysiology and Possible Remedies

Migraine is an incredibly complex disease involving a series of injury-induced alterations in the nervous system or nerve cells. Nerve fibers from the upper cervical roots and the trigeminal nucleus connect the dural vascular structures to the body86. Crucial to human sensation, the TGVS is composed primarily of pseudo-unipolar sensory neurons, as well as CSD. These nerves supply the major venous sinuses, dura mater, pial, and cerebral blood vessels. In the spinal trigeminal nucleus (SpV) and the trigeminal cervical complex (TCC), these structures project onto second-order neurons38. Subsequently, these fibers are transported to the sensory cortex and the thalamus. A confluence of trigeminal nerve fibers traveling through the TNC and upper cervical roots causes pain in the head and neck. In the hypothalamus, periaqueductal grey, locus querulous, and nucleus raphe magnum on the TNC, both ascending and descending fibers can affect pain perception. Unlike neuropeptides produced in the TG, such as CGRP, SP, and Neurokinin A (NKA), which are protected by the blood-brain barrier (BBB), these substances are allowed to cross the BBB into the systemic circulation87, 88, 89, 90.

In CSD, cells become depolarized in a slow, self-propagating wave. The disorder results in decreased neuronal activity as well as metabolic abnormalities in the cerebral cortex91. In CSD, neurons and glial cells are inhibited for a long duration owing to a progressive depolarization wave. It is marked by elevated K+ levels and decreased Na+ levels in the extracellular space. There are also changes in ions like Mg2+, Zn2+, and Cl- gradients92. These mechanisms stimulate TNC neurons, which can cause an inflammatory response in the meningeal vascular structures, resulting in headaches and pain. Matrix metalloproteinase overexpression changes occur in the brain. In this stage, sympathetic activation causes neurons to become active and responsive to a wide range of stimuli, including nociceptive ones. Consequently, peripheral sensitization occurs, meaning the body is more sensitive to non-noxious and noxious stimuli, as well as to an increase in pain receptor sites. It is unknown precisely where CSD arises from, but it is likely to result from increased extracellular K+ and glutamate, which activate dendritic spines without synaptic transmission93. There is a possibility that migraines are caused by CSD, and the aura associated with migraine might be caused by chronic stress disorder.

Currently, surgery, medication, physical therapy, and psychological therapy are the main methods used to relieve pain and enhance the quality of life. Over the past several decades, the use of medications, including opioids and non-opioids, has increased significantly. Medication abuse, tolerance, and addiction have all been associated with extensive use of such medications. There are a number of significant drawbacks of clinically available drugs that have led to a shift in the focus of drug development to improve the targeting of drugs, reduce the side effects, and extend the release of active compounds over time. The rapid metabolism of these current formulations, however, makes it difficult to manufacture them reproducibly, and the required dosage can cause physical side effects that are poorly tolerated. Pharmaceutical and nanotechnology integration has led to the development of more effective chronic pain treatments with fewer negative side effects.

Nanotechnology in Chronic Pain Relief

Due to their small size and large surface area, nanoscale materials are capable of providing new properties and functions beyond those of their bulkier equivalents, potentially causing changes in their physicochemical properties94, 95, 96, 97. As nanomaterials are advancing rapidly and have both positive and negative consequences on society and the environment, a variety of techniques are required to carry out toxicological evaluations. Pollutants emitted by the workplace may cause health problems for workers. Engineered nanomaterials (ENM) can be evaluated for their toxicological and immunological effects on certain cell types; they are commonly tested on dendritic cells, epithelial cells, or macrophages98, 99, 100, 101. ENM immunotoxicity tests should be standardized, and the effects on the body of the ENM should be studied further. ZnO nanoparticles stimulate eosinophils in the respiratory tract, which increases serum IgE levels. Nanoparticle exposure can also lead to the deficiency of oxygen in the body, caused by fibrosis and cellular hyperplasia98, 102, 103, 104. According to recent studies conducted on titanium dioxide nanoparticles, these particles may interact with cell signaling to trigger cell activation after their release from membrane-bound organelles. Nanomaterials such as metals, metal oxides, carbon nanotubes, fullerenes, polymer nanoparticles, and quantum dots have been the focus of much toxicology research105, 106, 107, 108, 109. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles were found to interact with the signaling system within membrane-bound organelles, ultimately activating cellular events110. Numerous studies have shown that nanoparticle changes, such as surface coatings, can alter the toxicological properties of an object. Nanoparticle safety and toxicity have been evaluated in vitro and in vivo in several studies111, 112, 113.

Based on all of its characteristics, a nanomaterial can be characterized as organic, inorganic, or metal-organic. With nanomaterials, proteins drugs and unbound free molecules can be encapsulated to provide long-lasting pain relief that is both controlled and sustained. Several pain-relief drugs have been developed using organic and inorganic non-targeted nanomaterials. PLGA carbon-based polymer nanomaterials pose the most concern for biocompatibility114. Due to their origin in cellular lipids, liposomes are highly biocompatible, and are well-studied. Emerging clinical trials have focused on liposome formulations; a PEGylated-liposome has been used to encapsulate zoledronic acid (ZOL), an inhibitor of Ras-dependent Erk-mediated pathways, and increase its degradation pathways to treat neuropathic pain115. A liposome-based delivery system allows crossing of the BBB, enabling ZOL to be released in a manner that effectively mitigates pain. Studies have investigated the neuropathic pain-relieving ability of dihydromorphinone and tested its encapsulation using liposomes. Liposomes boast several advantages over well-established alternatives. Nanomaterials provide a myriad of tunable properties, such as surface characteristics, responsiveness, regulated circulating duration, high loading efficiency, and the capacity to target specific tissues116. An excessive amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in an inflammatory site can lead to chronic pain, and has led to the development of nanomaterials that consume ROS117. The field of biomedicine and nanotechnology is also emphasizing the delivery of biomolecules, such as Ribonucleic Acid (RNA). PLGA nanomaterials were used to encapsulate the p38 siRNA in a study to enhance its firmness and delay its release in order to alleviate neuropathy118. The treatment of chronic pain with magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles was demonstrated in a study using inorganic nanoparticles. Researchers identified that these nanoparticles reduced pain at a statistically significant level, motivating further development.

Targeted Nanomaterials

The encapsulation of drugs as nanoparticles could provide effective treatment for chronic pain, but their limited efficacy has prompted researchers to search for more effective treatments. Depending on the treatment intervention, the type and dosing of drugs can be varied by enhancing the concentration of the drug at the intended site of action, potentially improving the efficacy of treatment and minimizing off-target effects. Nanomaterials can be modified; site-specific targeting is achieved using substances such as antibodies and peptides119. Moreover, the administration method is important and drug delivery of nanomaterials can be enhanced by surface modification. Enhancing the absorption of drugs can easily be achieved in this manner. Liposomes containing the opioid fentanyl that were delivered through aerosols demonstrated enhanced stability, enhanced analgesia, and improved pharmacokinetics. Lactoferrin and transferrin ligands have been used to modify PLGA nanomaterials so that they can be targeted to specific areas of the brain for pain relief120. The design of opioid-loaded liposomes that can target inflammatory environments while simultaneously releasing corresponding drugs is another approach to relieving pain. Neurokinin-1 receptors (NK1R) in the endosomes have been successfully targeted in a study121 that showed pH-responsive NK1R-containing endosomes produced sustained pain relief.

Nanomaterials for Autoimmune Diseases

Conventional nanomaterials are immune-mediated and can infiltrate tissues during autoimmune diseases, impairing both structural and functional efficacy122. Engineered nanomaterials enable the modulation of innate immune signals that initiate adaptive autoimmune reactions, as well as the modulation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Researchers found that macrophages were effectively treated by glucocorticoid-loaded liposomes at a much lower dose than conventional glucocorticoids in autoimmune encephalomyelitis123. Due to the antigenic complexity of autoimmune diseases and the need to target multiple factors of autoreactive T cells, conventional antigen-based therapies have several limitations. Nanoparticles coated with peptides that carry major histocompatibility complexes (MHC) have been shown to increase the number of CD4+ regulatory T cells. APCs that are autoantigen-loaded can be selectively removed by nanoparticles in the target tissue, inhibiting polyclonal autoimmune reactions. It is envisaged that there will be future generations of nano-based drugs for treating autoimmune diseases based on nanoparticles with multiple surfaces, as well as nanoparticles with single surfaces124, 125.

Effect of Nanomaterials on Immune Responses

Nanoparticles have properties such as size, hydrophobicity, surface charge, and coatings that are critical to modulating innate immunity, a non-specific, non-clonal, non-anticipatory system that is not derived from the germline. Nanomaterials used for treating diseases would also affect the immune system. The nature of adaptive immunity, meanwhile, is specific, clonal, physical, and anticipatory. A molecule on the surface of innate immune cells is required to stimulate them, not the NPs directly126. Antitumor chemotherapies contain NPs that are primarily absorbed by leukocytes. NPs are deformed when body molecules adsorb on their surface, causing an adaptive immune response. They are folded, deformed, and immunogenic when body molecules adsorb on their surface.

Conclusion

An initial migraine linkage gene was identified on chromosome 19p,19. Three different gene mutations associated with ion transport were discovered as a result. These mutations have been linked to FHM. Following that, three different gene mutations involved in ion transportation were discovered, and these mutations can cause familial hemiplegic migraine. Researchers reported that CACNA1A, ATP1A2, and SCN1A are the main genes related to FHM. As a result of their roles as ion channels and transport, along with functional experiments in cells and animals, identification of their malfunctions may contribute to the understanding of cortical hyperexcitability and migraine. However, developments in nanotechnology provide new opportunities for gene-to-molecule communication. Initially, candidate gene association studies (CGAS) were performed in order to identify genes linked to neuronal, vascular, and hormonal functions and to determine whether these genes affected migraine susceptibility. A nano-based delivery system was examined using CGAS to determine whether this approach altered migraine susceptibility. Genes were identified as promising for migraine treatment applications. Nanomedicines can also be used as prophylactic migraine treatments by targeting migraine pathways. Despite these advances, there is a need for more research to identify the targets involved in migraine pathophysiology.

Abbreviations

None.

Acknowledgments

CARE is acknowledged for infrastructural support, and PG thanks CARE for fellowships.

Author’s contributions

Collection of all required data and the initial draft was written by PG. KG and PP compiled it with additional data. The concept, overall representation, and final version were prepared by AG. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

-

Stovner

L.J.,

Nichols

E.,

Steiner

T.J.,

Abd-Allah

F.,

Abdelalim

A.,

Al-Raddadi

R.M.,

Headache Collaborators

GBD 2016,

Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurology.

2018;

17

(11)

:

954-76

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Kulkarni

A.R.,

Kulkarni

V.A.,

Study of Prevalence of Migraine Associated with CardioVascular Diseases in Women of Maharashtra Population. Indian Journal of Public Health Research & Development.

2019;

10

(8)

:

164

.

View Article Google Scholar -

L. Norcliffe-Kaufmann,

P.M. Vernetti,

J.A. Palma,

B.J. Balgobin,

H. Kaufmann,

Afferent baroreflex dysfunction: decreased or excessive signaling results in distinct phenotypes. Seminars in Neurology.

2020;

40

(5)

:

540-549

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Maagdenberg

A.M. Van Den,

Terwindt

G.M.,

Haan

J.,

Frants

R.R.,

Ferrari

M.D.,

Genetics of headaches. Handbook of Clinical Neurology.

2010;

97

:

85-97

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Antoniou

A.,

Pharoah

P.D.,

Narod

S.,

Risch

H.A.,

Eyfjord

J.E.,

Hopper

J.L.,

Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case Series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. American Journal of Human Genetics.

2003;

72

(5)

:

1117-30

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Sadler

M.E.,

Miller

C.J.,

Christensen

K.,

McGue

M.,

Subjective wellbeing and longevity: a co-twin control study. Twin Research and Human Genetics.

2011;

14

(3)

:

249-56

.

View Article Google Scholar -

de Vries

B.,

Frants

R.R.,

Ferrari

M.D.,

van den Maagdenberg

A.M.,

Molecular genetics of migraine. Human Genetics.

2009;

126

(1)

:

115-32

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Yiannopoulou

K.G.,

Efthymiou

A.,

Karydakis

K.,

Arhimandritis

A.,

Bovaretos

N.,

Tzivras

M.,

Helicobacter pylori infection as an environmental risk factor for migraine without aura. The Journal of Headache and Pain.

2007;

8

(6)

:

329-33

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Stuart

S.,

Cox

H.C.,

Lea

R.A.,

Griffiths

L.R.,

The role of the MTHFR gene in migraine. Headache.

2012;

52

(3)

:

515-20

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Stam

A.H.,

Kothari

P.H.,

Shaikh

A.,

Gschwendter

A.,

Jen

J.C.,

Hodgkinson

S.,

Retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukoencephalopathy and systemic manifestations. Brain.

2016;

139

(11)

:

2909-22

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Jasrotia

R.,

Kumar

P.,

Kundal

B.R.,

Langer

S.,

Insights into the role of epigenetic mechanisms in migraine: the future perspective of disease management. Nucleus (Austin, Tex.).

2021;

64

(3)

:

373-82

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Hamad

N.,

Alzoubi

K.H.,

Swedan

S.F.,

Khabour

O.F.,

El-Salem

K.,

Association between tumor necrosis factor alpha and lymphotoxin alpha gene polymorphisms and migraine occurrence among Jordanians. Neurological Sciences.

2021;

42

(9)

:

3625-30

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Polat

İ.,

Karaoğlu

P.,

\cSişman

A.R.,

Yiş

U.,

H\iz Kurul

S.,

Inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in pediatric migraine patients. Pediatrics International.

2022;

64

(1)

:

e14946

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Fu

X.,

Yang

J.,

Wu

X.,

Lin

Q.,

Zeng

Y.,

Xia

Q.,

Association between PRDM16, MEF2D, TRPM8, LRP1 gene polymorphisms and migraine susceptibility in the She ethnic population in China. Clinical and Investigative Medicine. Medecine Clinique et Experimentale.

2019;

42

(1)

:

21-30

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Farias

F.H.,

Dahlqvist

J.,

Kozyrev

S.V.,

Leonard

D.,

Wilbe

M.,

Abramov

S.N.,

A rare regulatory variant in the MEF2D gene affects gene regulation and splicing and is associated with a SLE sub-phenotype in Swedish cohorts. European Journal of Human Genetics.

2019;

27

(3)

:

432-41

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Choquet

H.,

Yin

J.,

Jacobson

A.S.,

Horton

B.H.,

Hoffmann

T.J.,

Jorgenson

E.,

New and sex-specific migraine susceptibility loci identified from a multiethnic genome-wide meta-analysis. Communications Biology.

2021;

4

(1)

:

864

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Jiang

Z.,

Zhao

L.,

Zhang

X.,

Zhang

W.,

Feng

Y.,

Li

T.,

Common variants in KCNK5 and FHL5 genes contributed to the susceptibility of migraine without aura in Han Chinese population. Scientific Reports.

2021;

11

(1)

:

6807

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Gavva

N.R.,

Sandrock

R.,

Arnold

G.E.,

Davis

M.,

Lamas

E.,

Lindvay

C.,

Reduced TRPM8 expression underpins reduced migraine risk and attenuated cold pain sensation in humans. Scientific Reports.

2019;

9

(1)

:

19655

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Kaur

S.,

Ali

A.,

Siahbalaei

Y.,

Ahmad

U.,

Pandey

A.K.,

Singh

B.,

Could rs4379368 be a genetic marker for North Indian migraine patients with aura?: preliminary evidence by a replication study. Neuroscience Letters.

2019;

712

:

134482

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Routman

D.M.,

Raghunathan

A.,

Giannini

C.,

Mahajan

A.,

Beltran

C.,

Nagib

M.G.,

Anaplastic ependymoma and posterior fossa grouping in a patient with H3K27ME3 loss of expression but chromosomal imbalance. Advances in Radiation Oncology.

2019;

4

(3)

:

466-72

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Al-Hassany

L.,

Haas

J.,

Piccininni

M.,

Kurth

T.,

Brink

A. Maassen Van Den,

Rohmann

J.L.,

Giving researchers a headache - sex and gender differences in migraine. Frontiers in Neurology.

2020;

11

:

549038

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Tsao

Y.C.,

Wang

S.J.,

Hsu

C.L.,

Wang

Y.F.,

Fuh

J.L.,

Chen

S.P.,

Genome-wide association study reveals susceptibility loci for self-reported headache in a large community-based Asian population. Cephalalgia.

2022;

42

(3)

:

229-38

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Siokas

V.,

Liampas

I.,

Aloizou

A.M.,

Papasavva

M.,

Bakirtzis

C.,

Lavdas

E.,

Deciphering the Role of the rs2651899, rs10166942, and rs11172113 Polymorphisms in Migraine: A Meta-Analysis. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania).

2022;

58

(4)

:

491

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Renthal

W.,

Localization of migraine susceptibility genes in human brain by single-cell RNA sequencing. Cephalalgia.

2018;

38

(13)

:

1976-83

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Lee

S.,

Lee

H.,

Yoo

S.,

Ieva

R.,

van der Laan

M.,

von Heijne

G.,

The Mgr2 subunit of the TIM23 complex regulates membrane insertion of marginal stop-transfer signals in the mitochondrial inner membrane. FEBS Letters.

2020;

594

(6)

:

1081-7

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Fila

M.,

Sobczuk

A.,

Pawlowska

E.,

Blasiak

J.,

Epigenetic Connection of the Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide and Its Potential in Migraine. International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

2022;

23

(11)

:

6151

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Rainero

I.,

Vacca

A.,

Govone

F.,

Gai

A.,

Pinessi

L.,

Rubino

E.,

Migraine: genetic variants and clinical phenotypes. Current Medicinal Chemistry.

2019;

26

(34)

:

6207-21

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Kowalska

M.,

Kapelusiak-Pielok

M.,

Grzelak

T.,

Wypasek

E.,

Kozubski

W.,

Dorszewska

J.,

The New *G29A and G1222A of HCRTR1, 5-HTTLPR of SLC6A4 Polymorphisms and Hypocretin-1, Serotonin Concentrations in Migraine Patients. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience.

2018;

11

:

191

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Rafi

S.K.,

Fernández-Jaén

A.,

Álvarez

S.,

Nadeau

O.W.,

Butler

M.G.,

High functioning autism with missense mutations in synaptotagmin-like protein 4 (SYTL4) and transmembrane protein 187 (TMEM187) genes: SYTL4-protein modeling, protein-protein interaction, expression profiling and microRNA studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

2019;

20

(13)

:

3358

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Naveed

M.,

Bukhari

B.,

Afzal

N.,

Sadia

H.,

Meer

B.,

Riaz

T.,

Geographical, Molecular, and Computational Analysis of Migraine-Causing Genes. Journal of Computational Biophysics and Chemistry..

2021;

20

(04)

:

391-403

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Pavinato

L.,

Nematian-Ardestani

E.,

Zonta

A.,

De Rubeis

S.,

Buxbaum

J.,

Mancini

C.,

KCNK18 biallelic variants associated with intellectual disability and neurodevelopmental disorders alter TRESK channel activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

2021;

22

(11)

:

6064

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Gur-Hartman

T.,

Berkowitz

O.,

Yosovich

K.,

Roubertie

A.,

Zanni

G.,

Macaya

A.,

Clinical phenotypes of infantile onset CACNA1A-related disorder. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology.

2021;

30

:

144-54

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Oda

I.,

Danno

D.,

Saigoh

K.,

Wolf

J.,

Kawashita

N.,

Hirano

M.,

Hemiplegic migraine type 2 with new mutation of the ATP1A2 gene in Japanese cases. Neuroscience Research.

2022;

180

:

83-9

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Santos

B.P. dos,

Maschi

B.,

Campos

G.R.,

Rossi

G.C.,

Ribeiro

G.E. de Pádua,

Volpato

G.M.,

Single nucleotide variants in the SCN1A gene and their relation to the development of type 3 familial hemiplegic migraine. Headache Medicine.

2022;

13

(S)

:

17

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Vahedi

K.,

Alamowitch

S.,

Clinical spectrum of type IV collagen (COL4A1) mutations: a novel genetic multisystem disease. Current Opinion in Neurology.

2011;

24

(1)

:

63-8

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Cullen

D.K.,

Vernekar

V.N.,

LaPlaca

M.C.,

Trauma-induced plasmalemma disruptions in three-dimensional neural cultures are dependent on strain modality and rate. Journal of Neurotrauma.

2011;

28

(11)

:

2219-33

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Di Filippo

M.,

Sarchielli

P.,

Picconi

B.,

Calabresi

P.,

Neuroinflammation and synaptic plasticity: theoretical basis for a novel, immune-centred, therapeutic approach to neurological disorders. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences.

2008;

29

(8)

:

402-12

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Dodick

D.W.,

A phase-by-phase review of migraine pathophysiology. Headache.

2018;

58

:

4-16

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Zhang

X.,

Levy

D.,

Kainz

V.,

Noseda

R.,

Jakubowski

M.,

Burstein

R.,

Activation of central trigeminovascular neurons by cortical spreading depression. Annals of Neurology.

2011;

69

(5)

:

855-65

.

View Article Google Scholar -

MacGregor

E.A.,

Migraine, menopause and hormone replacement therapy. Post Reproductive Health.

2018;

24

(1)

:

11-8

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Modena

B.D.,

Bleecker

E.R.,

Busse

W.W.,

Erzurum

S.C.,

Gaston

B.M.,

Jarjour

N.N.,

Gene expression correlated with severe asthma characteristics reveals heterogeneous mechanisms of severe disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

2017;

195

(11)

:

1449-63

.

View Article Google Scholar -

May

A.,

Ophoff

R.A.,

Terwindt

G.M.,

Urban

C.,

van Eijk

R.,

Haan

J.,

Familial hemiplegic migraine locus on 19p13 is involved in the common forms of migraine with and without aura. Human Genetics.

1995;

96

(5)

:

604-8

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Lechner

C.,

Taylor

R.L.,

Todd

C.,

Macdougall

H.,

Yavor

R.,

Halmagyi

G.M.,

Causes and characteristics of horizontal positional nystagmus. Journal of Neurology.

2014;

261

(5)

:

1009-17

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Russell

M.B.,

Ducros

A.,

Sporadic and familial hemiplegic migraine: pathophysiological mechanisms, clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Neurology.

2011;

10

(5)

:

457-70

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Vanmolkot

K.R.,

Kors

E.E.,

Hottenga

J.J.,

Terwindt

G.M.,

Haan

J.,

Hoefnagels

W.A.,

Novel mutations in the Na+, K+-ATPase pump gene ATP1A2 associated with familial hemiplegic migraine and benign familial infantile convulsions. Annals of Neurology.

2003;

54

(3)

:

360-6

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Romani

M.,

Micalizzi

A.,

Valente

E.M.,

Joubert syndrome: congenital cerebellar ataxia with the molar tooth. Lancet Neurology.

2013;

12

(9)

:

894-905

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Helbig

K.L.,

Lauerer

R.J.,

Bahr

J.C.,

Souza

I.A.,

Myers

C.T.,

Uysal

B.,

Genomics

Task Force for Neonatal,

Study

Deciphering Developmental Disorders,

De novo pathogenic variants in CACNA1E cause developmental and epileptic encephalopathy with contractures, macrocephaly, and dyskinesias. American Journal of Human Genetics.

2018;

103

(5)

:

666-78

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Prakash

T.P.,

Lima

W.F.,

Murray

H.M.,

Li

W.,

Kinberger

G.A.,

Chappell

A.E.,

Identification of metabolically stable 5'-phosphate analogs that support single-stranded siRNA activity. Nucleic Acids Research.

2015;

43

(6)

:

2993-3011

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Vargas

B.B.,

Acute treatment of migraine. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.).

2018;

24

(4)

:

1032-51

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Szklany

K.,

Ruiter

E.,

Mian

F.,

Kunze

W.,

Bienenstock

J.,

Forsythe

P.,

Superior cervical ganglia neurons induce Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via calcitonin gene-related peptide. PLoS One.

2016;

11

(3)

:

e0152443

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Raivich

G.,

Jones

L.,

Werner

A.,

Blüthmann

H.,

Doetschmann

T.,

Kreutzberg

G.,

Molecular signals for glial activation: pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the injured brain. Current Progress in the Understanding of Secondary Brain Damage from Trauma and Ischemia.

1999;

:

21-30

.

-

Schoenen

J.,

Jensen

R.H.,

Lantéri-Minet

M.,

Láinez

M.J.,

Gaul

C.,

Goodman

A.M.,

Stimulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) for cluster headache treatment. Pathway CH-1: a randomized, sham-controlled study. Cephalalgia.

2013;

33

(10)

:

816-30

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Haanes

K.A.,

Labastida-Ramírez

A.,

Blixt

F.W.,

Rubio-Beltrán

E.,

Dirven

C.M.,

Danser

A.H.,

Exploration of purinergic receptors as potential anti-migraine targets using established pre-clinical migraine models. Cephalalgia.

2019;

39

(11)

:

1421-34

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Yeoh

J.W.,

James

M.H.,

Adams

C.D.,

Bains

J.S.,

Sakurai

T.,

Aston-Jones

G.,

Activation of lateral hypothalamic group III metabotropic glutamate receptors suppresses cocaine-seeking following abstinence and normalizes drug-associated increases in excitatory drive to orexin/hypocretin cells. Neuropharmacology.

2019;

154

:

22-33

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Lambru

G.,

Andreou

A.P.,

Guglielmetti

M.,

Martelletti

P.,

Emerging drugs for migraine treatment: an update. Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs.

2018;

23

(4)

:

301-18

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Hendriksen

E.,

van Bergeijk

D.,

Oosting

R.S.,

Redegeld

F.A.,

Mast cells in neuroinflammation and brain disorders. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews.

2017;

79

:

119-33

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Iyengar

S.,

Johnson

K.W.,

Ossipov

M.H.,

Aurora

S.K.,

CGRP and the trigeminal system in migraine. Headache.

2019;

59

(5)

:

659-81

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Russo

A.F.,

Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP): a new target for migraine. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology.

2015;

55

(1)

:

533-52

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Iyengar

S.,

Ossipov

M.H.,

Johnson

K.W.,

The role of calcitonin gene-related peptide in peripheral and central pain mechanisms including migraine. Pain.

2017;

158

(4)

:

543-59

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Yu

M.L.,

Wei

R.D.,

Zhang

T.,

Wang

J.M.,

Cheng

Y.,

Qin

F.F.,

Electroacupuncture relieves pain and attenuates inflammation progression through inducing IL-10 production in CFA-induced mice. Inflammation.

2020;

43

(4)

:

1233-45

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Diasso

P.D.,

Birke

H.,

Nielsen

S.D.,

Main

K.M.,

H∅jsted

J.,

Sj∅gren

P.,

The effects of long-term opioid treatment on the immune system in chronic non-cancer pain patients: A systematic review. European Journal of Pain (London, England).

2020;

24

(3)

:

481-96

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Kim

C.M.,

Choi

J.Y.,

Bhat

E.A.,

Jeong

J.H.,

Son

Y.J.,

Kim

S.,

Crystal structure of TRAF1 TRAF domain and its implications in the TRAF1-mediated intracellular signaling pathway. Scientific Reports.

2016;

6

(1)

:

25526

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Yamani

N.,

Olesen

J.,

New daily persistent headache: a systematic review on an enigmatic disorder. The Journal of Headache and Pain.

2019;

20

(1)

:

80

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Chauhan

N.B.,

Chronic neurodegenerative consequences of traumatic brain injury. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience.

2014;

32

(2)

:

337-65

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Thuraiaiyah

J.,

Kokoti

L.,

Al-Karagholi

M.A.,

Ashina

M.,

Involvement of adenosine signaling pathway in migraine pathophysiology: a systematic review of preclinical studies. The Journal of Headache and Pain.

2022;

23

(1)

:

43

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Tajti

J.,

Szok

D.,

Nyári

A.,

Vécsei

L.,

CGRP and CGRP-receptor as targets of migraine therapy: Brain Prize-2021. CNS & Neurological Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-CNS & Neurological Disorders).

2022;

21

(6)

:

460-478

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Farmer

E.E.,

Gao

Y.Q.,

Lenzoni

G.,

Wolfender

J.L.,

Wu

Q.,

Wound- and mechanostimulated electrical signals control hormone responses. The New Phytologist.

2020;

227

(4)

:

1037-50

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Sutherland

H.G.,

Albury

C.L.,

Griffiths

L.R.,

Advances in genetics of migraine. The Journal of Headache and Pain.

2019;

20

(1)

:

72

.

View Article Google Scholar -

de Boer

I.,

van den Maagdenberg

A.M.,

Terwindt

G.M.,

Advance in genetics of migraine. Current Opinion in Neurology.

2019;

32

(3)

:

413-21

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Kowalska

M.,

Prendecki

M.,

Kapelusiak-Pielok

M.,

Grzelak

T.,

Łagan-Jędrzejczyk

U.,

Wiszniewska

M.,

Analysis of Genetic Variants in SCN1A, SCN2A, KCNK18, TRPA1 and STX1A as a Possible Marker of Migraine. Current Genomics.

2020;

21

(3)

:

224-36

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Allena

M.,

Icco

R. De,

Sances

G.,

Ahmad

L.,

Putorti

A.,

Pucci

E.,

Gender differences in the clinical presentation of cluster headache: a role for sexual hormones?. Frontiers in Neurology.

2019;

10

:

1220

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Dirven

B.C.,

Homberg

J.R.,

Kozicz

T.,

Henckens

M.J.,

Epigenetic programming of the neuroendocrine stress response by adult life stress. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology.

2017;

59

(1)

:

11-31

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Pajarillo

E.,

Rizor

A.,

Lee

J.,

Aschner

M.,

Lee

E.,

The role of astrocytic glutamate transporters GLT-1 and GLAST in neurological disorders: potential targets for neurotherapeutics. Neuropharmacology.

2019;

161

:

107559

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Sae-Lee

C.,

Corsi

S.,

Barrow

T.M.,

Kuhnle

G.G.,

Bollati

V.,

Mathers

J.C.,

Dietary intervention modifies DNA methylation age assessed by the epigenetic clock. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research.

2018;

62

(23)

:

e1800092

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Nolfi-Donegan

D.,

Braganza

A.,

Shiva

S.,

Mitochondrial electron transport chain: oxidative phosphorylation, oxidant production, and methods of measurement. Redox Biology.

2020;

37

:

101674

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Rangaraju

V.,

Lewis

T.L.,

Hirabayashi

Y.,

Bergami

M.,

Motori

E.,

Cartoni

R.,

Pleiotropic mitochondria: the influence of mitochondria on neuronal development and disease. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience.

2019;

39

(42)

:

8200-8

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Bennett

J.P.,

Keeney

P.M.,

Brohawn

D.G.,

RNA sequencing reveals small and variable contributions of infectious agents to transcriptomes of postmortem nervous tissues from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease subjects, and increased expression of genes from disease-activated microglia. Frontiers in Neuroscience.

2019;

13

:

235

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Pasquariello

R.,

Ermisch

A.F.,

Silva

E.,

McCormick

S.,

Logsdon

D.,

Barfield

J.P.,

Alterations in oocyte mitochondrial number and function are related to spindle defects and occur with maternal aging in mice and humans. Biology of Reproduction.

2019;

100

(4)

:

971-81

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Burch

R.,

Epidemiology and treatment of menstrual migraine and migraine during pregnancy and lactation: a narrative review. Headache.

2020;

60

(1)

:

200-16

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Quintas

M.,

Neto

J.L.,

Sequeiros

J.,

Sousa

A.,

Pereira-Monteiro

J.,

Lemos

C.,

Going deep into synaptic vesicle machinery genes and migraine susceptibility - A case-control association study. Headache.

2020;

60

(10)

:

2152-65

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Maher

B.H.,

Lea

R.A.,

Benton

M.,

Cox

H.C.,

Bellis

C.,

Carless

M.,

An X chromosome association scan of the Norfolk Island genetic isolate provides evidence for a novel migraine susceptibility locus at Xq12. PLoS One.

2012;

7

(5)

:

e37903

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Cukier

H.N.,

Dueker

N.D.,

Slifer

S.H.,

Lee

J.M.,

Whitehead

P.L.,

Lalanne

E.,

Exome sequencing of extended families with autism reveals genes shared across neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders. Molecular Autism.

2014;

5

(1)

:

1-10

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Dowling

M.M.,

Quinn

C.T.,

Ramaciotti

C.,

Kanter

J.,

Osunkwo

I.,

Inusa

B.,

Investigators

PFAST,

Increased prevalence of potential right-to-left shunting in children with sickle cell anaemia and stroke. British Journal of Haematology.

2017;

176

(2)

:

300-8

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Borgdorff

P.,

Arguments against the role of cortical spreading depression in migraine. Neurological Research.

2018;

40

(3)

:

173-81

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Negro

A.,

Delaruelle

Z.,

Ivanova

T.A.,

Khan

S.,

Ornello

R.,

Raffaelli

B.,

European Headache Federation School of Advanced Studies (EHF-SAS)

Headache and pregnancy: a systematic review. The Journal of Headache and Pain.

2017;

18

(1)

:

106

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Al-Ryalat

N.T.,

AlRyalat

S.A.,

Malkawi

L.W.,

Al-Zeena

E.F.,

Najar

M.S.,

Hadidy

A.M.,

Factors affecting attenuation of dural sinuses on noncontrasted computed tomography scan. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases.

2016;

25

(10)

:

2559-65

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Csekő

K.,

Beckers

B.,

Keszthelyi

D.,

Helyes

Z.,

Role of TRPV1 and TRPA1 ion channels in inflammatory bowel diseases: potential therapeutic targets?. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland).

2019;

12

(2)

:

48

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Brankatschk

M.,

Eaton

S.,

Lipoprotein particles cross the blood-brain barrier in Drosophila. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience.

2010;

30

(31)

:

10441-7

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Saucier-Sawyer

J.K.,

Deng

Y.,

Seo

Y.E.,

Cheng

C.J.,

Zhang

J.,

Quijano

E.,

Systemic delivery of blood-brain barrier-targeted polymeric nanoparticles enhances delivery to brain tissue. Journal of Drug Targeting.

2015;

23

(7-8)

:

736-49

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Chacko

A.M.,

Li

C.,

Pryma

D.A.,

Brem

S.,

Coukos