Abstract

Introduction: SIRT1 has attracted great interest due to its role as a regulator of longevity, and its therapeutic potential for the prevention and treatment of aging and age-related comorbidities. However, the mechanisms by which SIRT1 influences the course of aging remain unknown.

Methods: The study population included 88 apparently healthy subjects aged 31 ? 65 without established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or metabolic-associated diseases. Clinical, anthropometric, and biochemical parameters were determined in all patients. Molecular genetic studies included the determination of the C/G polymorphism of the SIRT1 gene (SIRT1, rs7069102), relative telomere length of blood leukocytes (RTL-b), and telomerase activity. Biological age was calculated using the DNAm PhenoAge epigenetic clock.

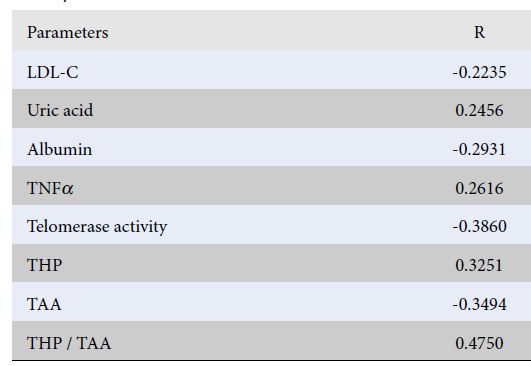

Results: The SIRT1 serum levels in carriers of different genotypes of the G/C polymorphism (rs7069102) and in patients of different age groups did not differ. SIRT1 plasma levels in the accelerated aging group were significantly higher in comparison with the healthy aging group: (4.16 ? 1.18) ng/ml vs (3.47 ? 0.76) ng/ml, respectively (p = 0.00066). Correlation analysis revealed a positive correlation of the SIRT1 serum level with uric acid (R = 0.25; p = 0.023), tissue necrosis factor (R = 0.26; p = 0.014), total hydroperoxides (R = 0.33; p = 0.003) and a negative correlation with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (R = -0.22; p = 0.039), telomerase activity (R = -0.39; p = 0.001) and total antioxidant activity (R = -0.35; p = 0.001). Stepwise regression analysis revealed negative association of the SIRT1 serum level with biological age.

Conclusion: SIRT1 plasma levels in apparently healthy subjects were associated with age, body mass index (BMI), WC, factors of carbohydrate metabolism, and markers of the pro-antioxidant balance. A comparative analysis of SIRT1 plasma levels between accelerated and healthy aging groups showed a significant difference. However, our study did not confirm that SNPs (rs7069102) of the SIRT1 genotypes are associated with SIRT1 plasma level, aging rate, or any metabolic parameters.

INTRODUCTION

Population aging is a significant challenge for modern societies. This demographic problem will increase the prevalence of many age-related chronic diseases and geriatric conditions. Sirtuin is an essential factor that influences cellular senescence and extends the organismal lifespan by regulating diverse cellular processes. Sirtuins have been actively investigated for over 20 years for their function in influencing cellular senescence and extending longevity.

Sirtuins (Silent Information Regulator Two, Sir2 proteins, SIRTs) are a class of proteins with properties of histone deacetylases and mono-ribosyltransferases. These are highly conserved NAD-dependent proteins found in all organisms, from bacteria to humans. Mammalian SIRTs (SIRT1-7), are classified by their highly conserved central NAD+ binding and catalytic domains and may have various biological functions. There are also differences in the expression of SIRTs in different tissues. It has been established that SIRTs regulate the processes of transcription and apoptosis, play an important role in the stress response of organisms (for example, heat shock or starvation), and are responsible for prolonging life in some animals. The metabolic regulation and cellular defense mechanisms in which they are involved can be used to influence the aging process and increase lifespan1, 2, 3.

Aging processes are closely related to atherosclerosis, the most common cause of death in the elderly, as well as to diabetes, dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome, and hypertension. The development of atherosclerosis is stimulated by SIRT1 deficiency in endothelial cells, smooth cells, and monocytes/macrophages. This results in the activation of processes such as oxidative stress, inflammation, formation of foam cells, and disruption of autophagy processes in the vascular wall. In turn, excessive autophagy, stimulated by high levels of inflammation or oxidative stress, contributes to a decrease in collagen synthesis, thinning of the fibrous cap, destabilization of plaque, restenosis, and the development of acute coronary syndrome. Studies have shown that SIRT1 elicits an atheroprotective effect by increasing the level of nitric oxide, degradation of liver kinase B1, blocking NF-kB (nuclear factor-kappa B) - mediated inflammatory process, reducing the intensity of oxidative stress, and controlling autophagy4. Another mechanism of the atheroprotective action of SIRT1 is associated with preventing the destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques by affecting the activity of metalloproteinase nine and supporting collagen synthesis in smooth muscle cells5.

SIRT1 expression declines with age at the protein and transcription levels in animal and human tissues, including the liver, heart, kidneys, brain, and lungs. Similarly, various in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that SIRT1 expression in senescent vascular tissues is significantly reduced, and SIRT1 deficiency in endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and macrophages accelerates vasculature aging. In favor of these processes, pre-treatment with the SIRT1 activator resveratrol significantly reduces reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, inhibits apoptosis, and promotes cell survival in myoblast cells. Overexpression of SIRT1 plays a role in inhibiting nucleus pulposus cell senescence, promoting cell proliferation, and suppressing apoptosis, and SIRT1 itself extends the lifespan of mice (by 9 and 16 % in males and females, respectively) when overexpressed in the brain. In addition, SIRT1 activation also suppresses UV-induced senescence of human skin fibroblasts. Thus, SIRT1 has attracted enormous interest due to its role as a longevity regulator and therapeutic potential for the prevention and treatment of aging and concomitant age-related diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disorders6, 7, 8, 9.

While SIRT1 is an interesting target molecule to study, for its potential to influence the aging process and promote health, the role of SIRT1 in longevity remains controversial. Also, data on the association of SIRT1 gene polymorphism with the level of SIRT1 in blood serum, and on the association of the SIRT1 gene's effect on the aging process remains elusive, especially in clinical studies.

Thus, the aim of our study was to determine the relationship between SIRT1 plasma level and SIRT1 SNPs with metabolic parameters and the rate of aging. The study also aimed to assess the possibility of using these parameters as markers/predictors of accelerated aging and the risk of developing metabolic diseases.

METHODS

This study was performed at the Department of the Study of Aging Processes and Prevention of Metabolically Associated Diseases of the L.T. Mala Therapy National Institute of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine (NIT NAMSU).

Characteristics of study participants

The research protocol was approved at a meeting of the Ethics Commission of the L.T. Mala NIT NAMSU in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed informed consent prior to any study-related procedures. The study group consisted of 88 apparently healthy subjects aged 47.6 [39.5; 54.7] 31-65 years old. There were 41 men (46.6 %) and 47 women (53.4 %) without established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ACVD), metabolic disease (diabetes mellitus, obesity) or other chronic diseases who did not receive any drug therapy were screened. Exclusion criteria included a history of chronic disease, patient failure to follow study procedures, alcohol or drug abuse, and clinically significant laboratory abnormalities. Anthropometric studies were carried out according to standard methods. BMI was calculated using the formula body weight (kg) / height (m)2. Body composition was determined by the bioelectrical impedance method using Composition Monitor BF511, Omron; body fat percentage (FAT, %), skeletal muscle percentage (MUS, %), and visceral fat level (VIS, %). Clinical blood analysis was performed on a MYTHIC18 automatic hematology analyzer. The content of insulin, C-reactive protein (CRP), tissue necrosis factor α (TNFα) and SIRT1 in blood serum was determined by the immunoenzymatic method using appropriate sets of reagents. The activity of total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD) in blood serum was determined by the colorimetric method. Blood lipid spectrum — total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglycerides (TG) were determined by the enzymatic method using Cormay (Poland) reagent sets. The glycosylated hemoglobin content (%) (HbA1c) was determined via the photometric ion exchange method. The pro-oxidant/antioxidant balance of blood serum was calculated as the ratio of the content of total hydroperoxides (THP) and total antioxidant activity (TAA). Molecular genetic studies included the determination of the C/G polymorphism of the sirtuin gene (SIRT1, rs7069102), relative telomere length of blood leukocytes (RTL-b), and telomerase activity. Genotyping of the C/G polymorphic site of the sirtuin gene (SIRT1, rs7069102) was performed by real-time PCR. Telomere length was determined by real-time PCR10, 11. Amplification was performed using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad Laboratories, USA) and primer system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Telomerase activity was determined by real-time PCR using the TRAPeze Kit RT Telomerase Detection Kit (Millipore, USA, CAT. No. S7710). Epigenetic age was calculated using the DNAm PhenoAge epigenetic clock based on nine biological markers: albumin (g/l); creatinine (mg/dL); glucose (mg/dL); CRP (mg/l); lymphocytes (%); Red Cell Distribution Width (RCDW) (%); Mean Cell Volume (MCV); alkaline phosphatase (U/l); leukocytes (x109/l); age (years).

Continuous variables obtained from the participants in this study were expressed as means ± SDs. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages. Data were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test (for continuous variables) and the chi-square test (for categorical variables). To assess the interrelationship of indicators, a correlation analysis was performed with the calculation of pairwise correlation coefficients. Also, the associations between variables were assessed using linear multiple regression models. When estimating regression equations, the method of stepwise inclusion of predictors was used, which ranks features in accordance with their contribution to the model. The overall agreement between the model and the real data was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow Goodness-of-Fit Test. The Bonferroni test was used to correct for multiple comparisons for all analyses. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted via the statistical package STATISTIСA V10.0.

| Characteristics | Groups | M-W p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerated ageing, n = 21 | Healthy ageing, n = 67 | ||

| HbA1c, % | 5.96 ± 0.21 | 5.65 ± 0.48 | 0.007891 |

| FPG, mmol/L | 6.03 ± 0.67 | 5.23 ± 0.53 | 0.000001 |

| Insulin, mMU/L | 28.84 ± 11.46 | 20.07 ± 9.69 | 0.005124 |

| HOMA IR | 7.47 ± 3.06 | 4.76 ± 2.59 | 0.000849 |

| TG, mmol/l | 1.87 ± 0.78 | 1.36 ± 0.78 | 0.006248 |

| TC, mmol/L | 5.65 ± 1.45 | 5.64 ± 1.11 | 0.967165 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 3.64 ± 1.30 | 3.58 ± 0.97 | 0.934385 |

| VLDL-C, mmol/L | 0.92 ± 0.52 | 0.63 ± 0.36 | 0.009185 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.21 ± 0.26 | 1.41 ± 0.31 | 0.007328 |

| Uric acid, µmol/L | 5.65 ± 1.45 | 5.64 ± 1.11 | 0.967165 |

| Albumin, g/L | 339.18 ± 62.71 | 250.94 ± 64.89 | 0.000022 |

| SIRT1, ng/ml | 4.16 ± 1.18 | 3.47 ± 0.76 | 0.000662 |

| TNFα, pg/ml | 2.84 ± 1.37 | 2.36 ± 0.98 | 0.251498 |

| T-SOD | 49.75 ± 5.40 | 49.06 ± 4.15 | 0.432705 |

| THP, µmol/l | 153.32 ± 66.87 | 125.55 ± 44.88 | 0.693237 |

| TAA, µmol trolox equivalent | 484.92 ± 146.95 | 546.09 ± 160.27 | 0.176598 |

| RTL-b, relative units | 0.97 ± 0.28 | 1.00 ± 0.28 | 0.790882 |

RESULTS

To determine the factors influencing aging rates, biological age (BA) was calculated using the DNAm PhenoAge epigenetic clock based on nine biological markers. After calculating BA, the rates of aging were determined for each examinee. If the patient's BA exceeded the calendar age by more than a year, the patient was assigned to the group of accelerated aging. If this was less than or equal to a year the patient was assigned to the group of healthy aging.

A comparative analysis of SIRT1 plasma levels revealed a difference between the accelerated and healthy aging groups. Accelerated aging was accompanied by a small but highly significant increase in SIRT1, which may indicate the activation of SIRT1-mediated metabolic pathways (Table 1). These groups also differed in a few biochemical indicators characterizing the state of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, as well as the pro-antioxidant balance (Table 1).

The influence of SIRT1 gene polymorphisms has already been studied, but there is still no consensus on the association of various SIRT1 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with the rate of aging and a predisposition to age-related diseases in humans. When choosing SIRT1 SNP, we proceeded from the fact that the results of the distribution of SNP polymorphisms rs2273773, rs3740051, and rs3758391 did not differ in mortality or age, as well as between frail and strong groups in senile frailty syndrome12, 13, 14, 15. Therefore, we decided to investigate SIRT1 SNP rs7069102 C>G polymorphisms located in intron 4, which elicited the most significant association with ACVD. SIRT1 SNP rs7069102 C>G was associated with an increased risk of subclinical coronary heart disease, an increase in the level of circulating SIRT1, and reduced expression of eNOS16, 17. The possible association of the SIRT1 SNP with a wide range of diseases and various pathological conditions may be consistent with the influence on the course of aging, which affects the susceptibility to many age-related diseases. The gene encoding SIRT1 may be closely associated with a risk of developing or the presence of diseases associated with metabolism, in particular, type 2 diabetes. This is because SIRT1 increases insulin secretion and fat deposition, affects insulin resistance, and is involved in regulating the metabolism of glucose and lipids by deacetylation of the histones of the corresponding transcription factors or target genes12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23.

| Genotype, allele | n = 88 | % |

|---|---|---|

| С/С | 5 | 5.68 |

| C/G | 45 | 51.13 |

| G/G | 38 | 43.18 |

| C allele | 55 | 31.25 |

| G allele | 121 | 68.75 |

| № | Genotype | N | SIRT1, ng/ml | Р (M-W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | С/С | 5 | 3.37 ± 0.24 | p1-2 = 0.741 |

| 2 | C/G | 44 | 3.62 ± 0.91 | p1-3 = 0.969 |

| 3 | G/G | 37 | 3.57 ± 0.89 | p2-3 = 0.842 |

| № group | Age, years | SIRT1, ng/ml | M-W |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Up to 45 (n = 32) | 3.55 ± 0.97 | p1-2 = 0.343 |

| 2 | 45-59 (n = 52) | 3.61 ± 0.84 | p1-3 = 0.633 |

| 3 | More than 60 (n = 4) | 3.42 ± 0.26 | p2-3 = 0.987 |

| Parameters | R | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| LDL-C | -0.2235 | 0.039 |

| Uric acid | 0.2456 | 0.023 |

| Albumin | -0.2931 | 0.006 |

| TNFα | 0.2616 | 0.014 |

| Telomerase activity | -0.3860 | 0.001 |

| THP | 0.3251 | 0.003 |

| TAA | -0.3494 | 0.001 |

| THP / TAA | 0.4750 | 0.001 |

| Parameters | b* ± Standard Error of b* Std.Err.[TMFSBTZ1] [ОЗ2] | b ± Standard Error of b | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 6.372 ± 1.214 | 0.000001 | |

| THP / TAA | 0.513 ± 0.080 | 1.764 ± 0.274 | 0.000000 |

| Age | -0.158 ± 0.079 | -0.011 ± 0.006 | 0.048 |

| Uric acid | 0.244 ± 0.088 | 0.003 ± 0.001 | 0.007 |

| Monocytes | 0.292 ± 0.082 | 0.123 ± 0.034 | 0.001 |

| Albumin | -0.241 ± 0.083 | -0.026 ± 0.009 | 0.005 |

| RDW | -0.252 ± 0.079 | -0.186 ± 0.058 | 0.002 |

| Al AT | -0.239 ± 0.093 | -0.009 ± 0.004 | 0.012 |

| Leukocytes | 0.179 ± 0.088 | 0.077 ± 0.038 | 0.044 |

| BMI | -0.306 ± 0.128 | -0.049 ± 0.021 | 0.019 |

| Insulin | 0.193 ± 0.100 | 0.013 ± 0.007 | 0.058 |

| HbA1c | -0.161 ± 0.081 | -0.310 ± 0.157 | 0.051 |

| Waist circumference | 0.243 ± 0.137 | 0.014 ± 0.008 | 0.079 |

| RTL-b | 0.108 ± 0.078 | 0.456 ± 0.331 | 0.173 |

When assessing the frequencies of G/G, C/G, and C/C genotypes of the SIRT1 SNP rs7069102 gene among individuals of the study group (Table 2), we found that results did not deviate from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p = 0.075).

The frequency of occurrence of the minor C allele was equal to 0.313 and did not significantly differ from the data of ALFA Allele Frequency (0.327) for the European population (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/rs7069102) and from the results for residents of Podillia, men without signs of cardiovascular pathology (0.350)24.

When analyzing the serum content of SIRT1 in carriers of different genotypes of the G/C polymorphism (rs7069102) of the SIRT1 gene, no significant differences between the study groups were found (Table 3).

In order to identify factors that may be associated with the presence of certain variants of the G/C polymorphism (rs7069102) of the SIRT1 gene, a comparative analysis of biochemical indicators was conducted in groups of patients carrying different genotypes of the specified polymorphism. Due to the low representation of C/C genotype carriers (n = 5), they were combined with C/G heterozygotes.

When conducting a comparative analysis of all defined indicators between groups, it was found that carriers of allele C had significantly higher activity of T-SOD (significance level p < 0.1) (p = 0.055) and shorter RTL-b (p = 0.102). No differences were found in the rest of the indicators.

It is known that the association of SIRT1 activity with life expectancy and SIRT1 expression declines with age. Therefore, we performed a comparative analysis of the serum level of SIRT1 in patients of different age groups. All patients were divided into groups depending on calendar age: group 1 — up to 45 years and below (n = 32), group 2 — from 45 years to 59 years (n = 52), and group 3 — over 60 years (n = 4). We found no significant differences in serum SIRT-1 between these groups (Table 4).

In order to measure the effect of SIRT1 on the regulation of metabolic pathways of aging, a correlation analysis was performed to determine the relationship between the serum level of SIRT1 and the primary metabolic and age parameters (Table 5).

Multivariate linear regression analysis was performed to establish both metabolic and molecular genetic factors associated with serum SIRT1 levels. (Table 6).

When conducting a dispersion analysis of the model and its significance, it was established that the contribution of the factors included in the model (Regress.= 28.56224) is 60.3% of the total sum of squared deviations of the predicted parameter (Total = 47.33818). In comparison, 39.7% of the contribution is due to random factors (Residual = 18.77595), which indicates the significance of the obtained model (F = 8.659218, p = 0.0000001).

DISCUSSION

According to recent studies, SIRT1 plays a crucial role in metabolism, immune response, oxidative status, and aging. SIRT1 regulates diverse cellular processes, including DNA repair, fat differentiation, glucose output, insulin sensitivity, fatty acid oxidation, neurogenesis, inflammation, and longevity25, 26, 27. It is also believed that SIRT1 may indirectly affect aging processes through the relationship between nutrition and aging10, 11, 12, 13. A study by Balestrieri et al. suggested that upregulation of SIRT1, which plays a key role as a metabolic sensor regulating glucose metabolism, may counteract the adverse effects associated with aging by reducing cardiovascular risk factors and28. In our study of apparently healthy subjects, we showed a significant association of SIRT1 with main metabolic factors, factors of pro-antioxidant balance and immune response: uric acid (R = 0.25; p = 0.023), TNFα (R = 0.26; p = 0.014), THP (R = 0.33; p = 0.003) and negative correlation with LDL-C (R = -0.22; p = 0.039), and TAA (R = -0.35; p = 0.001). The relationship between SIRT1 and telomerase activity was also confirmed (R = -0.39; p = 0.001).

Data on the effect of SIRT1 genotypes on SIRT-associated mechanisms of aging and on metabolic and age-related diseases, are contradictory29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35. Several studies have shown that various SIRT1 gene polymorphisms are associated with a predisposition to obesity32, arterial hypertension, and an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, including carotid atherosclerosis33, 34, 35. Kilik et al. demonstrated a strong association between SNPs (rs7895833) of SIRT1 genotypes with lifespan: the oldest individuals (age ≥ 76.0 years) were carriers of AG genotypes for (rs7895833) and showed the highest SIRT1 levels and lifespan29. The results of the Rotterdam study showed an association of SIRT1 genotypes with BMI. In addition, Peters et al. showed that carriers of the rs7069102 G allele of the SIRT1 gene have a higher risk of obesity than carriers of the C allele variant32. However, our data did not confirm this association. The results of our study did not demonstrate an association of the SIRT1 genotype SNP (rs7069102) with either plasma SIRT1 levels, metabolic parameters, or chronological/epigenetic age. Some studies showed similar results and did not reveal a significant influence of the SIRT1 genotype. A study of centenarians (mean age 102.4 ± 2.3 years) conducted in China showed that eight common SIRT1 polymorphisms were not associated with human longevity. Meta-analysis of the role of SIRT1 (rs3758391) polymorphism, C vs T allele, did also not reveal a significant effect of these polymorphism alleles on life expectancy11, 30, 31. Such contradictory research results do not currently have a clear explanation. This may be due to the subjects included in the study. All these associations were found in individuals with a high risk of or existing chronic disease (ACVD, obesity, neurogenerative diseases), but were not confirmed in apparently healthy individuals. This may be why our study of apparently healthy individuals did not confirm that SNPs (rs7069102) of SIRT1 genotypes are associated with any metabolic parameters and the rate of aging. This issue, therefore, requires further study.

Experimental models have shown that SIRT1 may be involved in the mechanisms that inhibit the progression of atherosclerosis and provide protection against ACVD by inhibiting chemotaxis of mononuclear cells36, adhesion to the vascular wall37, formation of foam cells36, oxidative stress38 and anti-inflammatory factors39. At the same time, many questions remain regarding how to realize the protective and anti-aging effects of SIRT140, 41.

The attempts in clinical trials to interpret SIRT1 plasma levels in pathology compared with controls have been controversial: in some trials, SIRT1 plasma levels decreased, while in others, the levels increased compared with controls. For example, in the trial including obese patients, the level of SIRT1 was significantly lower (P = 0.002) in patients with obesity compared with lean controls42. Also, in the study by Esmayel I.M et al. (2021), the SIRT1 levels in patients with acute ischemic stroke were significantly lower than in the control group43. In contrast, opposite reports were observed in the other two trials. The SIRT1 level was significantly increased in the acute ischemic stroke group compared with the control group (0.63 ± 0.75 vs 0.48 ± 0.80 ng/mL; P ≤ 0.05) in the study by Liu Y et al.44. In the study by Liang X. et al., serum SIRT1 was significantly higher (P = 0.036) in acute ischemic stroke patients (0.62 ± 0.77 ng/mL) compared to healthy control subjects (0.45 ± 0.69 ng/mL), but SIRT1 concentrations were not significantly higher (0.58 ± 0.69 versus 0.64 ± 0.81 ng/mL, P = 0.298) than in patients in the unfavorable functional outcome group45.

Our results showed that in apparently healthy subjects, the SIRT1 level was higher in the accelerated aging group, in contrast to the healthy aging group (4.16 ± 1.18) ng/ml vs (3.47 ± 0.76) ng/ml, (p=0.00066), respectively.

Stepwise multivariate linear regression analysis shows the model (p=0.0000001) that supports multiple associations of SIRT1 with the primary metabolic processes in the development of aging and age-related disease (atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, cancer, and others).

Conclusions

SIRT1 plasma levels in apparently healthy subjects were associated with age, BMI, and WC, factors of carbohydrate metabolism, and markers of the pro-antioxidant balance. A comparative analysis of SIRT1 plasma levels between accelerated and healthy aging groups (by DNAm PhenoAge epigenetic clock) showed a significant difference. These groups also differed by metabolic parameters (HOMA IR, Hb1 AC, FPG, TG, VLDL-C, HDL-C). However, our study of apparently healthy subjects did not confirm that SNPs (rs7069102) of the SIRT1 genotypes are associated with SIRT1 plasma level, aging rate, or metabolic parameters.

Abbreviations

ACVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; BA: biological age; BMI: index body mass; CAD: coronary artery disease; CRP: C-reactive protein; CVD: cardiovascular disease; HbA1c: glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL-C: cholesterol of high density lipoprotein; HOMA IR: Homeostatic Model Assessment of insulin resistance; FAT: body fat percentage; FPG: fasting plasma glucose; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MAD: metabolically associated disease; MCV: Mean Cell Volume; MUS: skeletal muscle percentage; RCDW: Red Cell Distribution Width; RTL-b: Relative telomere length of blood leukocytes; SD: standard deviation; SIRT1: sirtuin 1, SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism, TAA: total antioxidant activity; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; THP: total hydroperoxides; TNFα: tissue necrosis factor α; T-SOD: total superoxide dismutase activity; VIS: visceral fat level; VLDL-C: very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Acknowledgments

None.

Author’s contributions

Olena Kolesnikova: Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; Final approval of the version to be published; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Olga Zaprovalna: Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; Final approval of the version to be published; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Anastasiia Radchenko: the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; Final approval of the version to be published; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Tetiana Bondar: Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; Final approval of the version to be published; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review board approved the study, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

-

Mouchiroud

L.,

Houtkooper

R.H.,

Moullan

N.,

Katsyuba

E.,

Ryu

D.,

Cantó

C.,

The NAD(+)/Sirtuin Pathway Modulates Longevity through Activation of Mitochondrial UPR and FOXO Signaling. Cell.

2013;

154

(2)

:

430-41

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Pan

H.,

Finkel

T.,

Key proteins and pathways that regulate lifespan. The Journal of Biological Chemistry.

2017;

292

(16)

:

6452-60

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

van de Ven

R.A.,

Santos

D.,

Haigis

M.C.,

Mitochondrial Sirtuins and Molecular Mechanisms of Aging. Trends in Molecular Medicine.

2017;

23

(4)

:

320-31

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Lee

I.H.,

Mechanisms and disease implications of sirtuin-mediated autophagic regulation. Experimental & Molecular Medicine.

2019;

51

(9)

:

1-11

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Zhang

Y.,

Sun

J.,

Yu

X.,

Shi

L.,

Du

W.,

Hu

L.,

SIRT1 regulates accumulation of oxidized LDL in HUVEC via the autophagy-lysosomal pathway. Prostaglandins & Other Lipid Mediators.

2016;

122

:

37-44

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Chen

C.,

Zhou

M.,

Ge

Y.,

Wang

X.,

SIRT1 and aging related signaling pathways. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development.

2020;

187

:

111215

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Guo

J.,

Shao

M.,

Lu

F.,

Jiang

J.,

Xia

X.,

Role of SIRT1 plays in nucleus pulposus cells and intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa (1976).

2017;

42

(13)

:

E757-E766

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Pardo

P.S.,

Boriek

A.M.,

SIRT1 regulation in ageing and obesity. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development.

2020;

188

:

111249

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Costa

D.,

Scognamiglio

M.,

Fiorito

C.,

Benincasa

G.,

Napoli

C.,

Genetic background, epigenetic factors and dietary interventions which influence human longevity. Biogerontology.

2019;

20

(5)

:

605-26

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Cawthon

R.M.,

Telomere length measurement by a novel monochrome multiplex quantitative PCR method. Nucleic Acids Research.

2009;

37

(3)

:

e21

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Weischer

M.,

Bojesen

S.E.,

Cawthon

R.M.,

Freiberg

J.J.,

Tybj\aerg-Hansen

A.,

Nordestgaard

B.G.,

Short telomere length, myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and early death. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology.

2012;

32

(3)

:

822-9

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Razi

S.,

Cogger

V.C.,

Kennerson

M.,

Benson

V.L.,

McMahon

A.C.,

Blyth

F.M.,

Handelsman

D.J.,

Seibel

M.J.,

Hirani

V.,

Naganathan

V.,

Waite

L.,

SIRT1 polymorphisms and serum-induced SIRT1 protein expression in aging and frailty: the CHAMP study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A.

2017;

72

(7)

:

870-6

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Han

J.,

Atzmon

G.,

Barzilai

N.,

Suh

Y.,

Genetic variation in Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) is associated with lipid profiles but not with longevity in Ashkenazi Jews. Translational Research ; the Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine.

2015;

165

(4)

:

480-1

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Huang

J.,

Sun

L.,

Liu

M.,

Zhou

L.,

Lv

Z.P.,

Hu

C.Y.,

[Association between SIRT1 gene polymorphisms and longevity of populations from Yongfu region of Guangxi]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi.

2013;

30

(1)

:

55-9

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Flachsbart

F.,

Croucher

P.J.,

Nikolaus

S.,

Hampe

J.,

Cordes

C.,

Schreiber

S.,

Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) sequence variation is not associated with exceptional human longevity. Experimental Gerontology.

2006;

41

(1)

:

98-102

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Ministrini

S.,

Puspitasari

Y.M.,

Beer

G.,

Liberale

L.,

Montecucco

F.,

Camici

G.G.,

Sirtuin 1 in Endothelial Dysfunction and Cardiovascular Aging. Frontiers in Physiology.

2021;

12

:

733696

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kilic

U.,

Gok

O.,

Bacaksiz

A.,

Izmirli

M.,

Elibol-Can

B.,

Uysal

O.,

SIRT1 gene polymorphisms affect the protein expression in cardiovascular diseases. PLoS One.

2014;

9

(2)

:

e90428

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Nasiri

M.,

Rauf

M.,

Kamfiroozie

H.,

Zibaeenezhad

M.J.,

Jamali

Z.,

SIRT1 gene polymorphisms associated with decreased risk of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. Gene.

2018;

672

:

16-20

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kedenko

L.,

Lamina

C.,

Kedenko

I.,

Kollerits

B.,

Kiesslich

T.,

Iglseder

B.,

Genetic polymorphisms at SIRT1 and FOXO1 are associated with carotid atherosclerosis in the SAPHIR cohort. BMC Medical Genetics.

2014;

15

(1)

:

112

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Hu

Y.,

Wang

L.,

Chen

S.,

Liu

X.,

Li

H.,

Lu

X.,

Association between the SIRT1 mRNA expression and acute coronary syndrome. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis.

2015;

22

(2)

:

165-82

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Ren

X.,

Chen

N.,

Chen

Y.,

Liu

W.,

Hu

Y.,

TRB3 stimulates SIRT1 degradation and induces insulin resistance by lipotoxicity via COP1. Experimental Cell Research.

2019;

382

(1)

:

111428

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Najt

C.P.,

Khan

S.A.,

Heden

T.D.,

Witthuhn

B.A.,

Perez

M.,

Heier

J.L.,

Lipid Droplet-Derived Monounsaturated Fatty Acids Traffic via PLIN5 to Allosterically Activate SIRT1. Molecular Cell.

2020;

77

(4)

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Zang

Y.,

Fan

L.,

Chen

J.,

Huang

R.,

Qin

H.,

Improvement of Lipid and Glucose Metabolism by Capsiate in Palmitic Acid-Treated HepG2 Cells via Activation of the AMPK/SIRT1 Signaling Pathway. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.

2018;

66

(26)

:

6772-81

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kalinovskaya

T.M.,

Donets

A.O.,

Zhebel

V.M.,

SIRT1 gene polymorphism and its plasma concentration in men with no signs of cardiovascular pathology, residents of Podilia region of Ukraine. Reports of Vinnytsia National Medical University.

2021;

25

(2)

:

215-9

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Lee

S.H.,

Lee

J.H.,

Lee

H.Y.,

Min

K.J.,

Sirtuin signaling in cellular senescence and aging. BMB Reports.

2019;

52

(1)

:

24-34

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

North

B.J.,

Verdin

E.,

Sirtuins: Sir2-related NAD-dependent protein deacetylases. Genome Biology.

2004;

5

(5)

:

224

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Toiber

D.,

Sebastian

C.,

Mostoslavsky

R.,

Characterization of nuclear sirtuins: molecular mechanisms and physiological relevance. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology.

2011;

206

:

189-224

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Balestrieri

M.L.,

Rienzo

M.,

Felice

F.,

Rossiello

R.,

Grimaldi

V.,

Milone

L.,

High glucose downregulates endothelial progenitor cell number via SIRT1. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta.

2008;

1784

(6)

:

936-45

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kilic

U.,

Gok

O.,

Erenberk

U.,

Dundaroz

M.R.,

Torun

E.,

Kucukardali

Y.,

A remarkable age-related increase in SIRT1 protein expression against oxidative stress in elderly: SIRT1 gene variants and longevity in human. PLoS One.

2015;

10

(3)

:

e0117954

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Lin

R.,

Yan

D.,

Zhang

Y.,

Liao

X.,

Gong

G.,

Hu

J.,

Common variants in SIRT1 and human longevity in a Chinese population. BMC Medical Genetics.

2016;

17

(1)

:

31

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Costa

D.,

Scognamiglio

M.,

Fiorito

C.,

Benincasa

G.,

Napoli

C.,

Genetic background, epigenetic factors and dietary interventions which influence human longevity. Biogerontology.

2019;

20

(5)

:

605-26

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Peeters

A.V.,

Beckers

S.,

Verrijken

A.,

Mertens

I.,

Roevens

P.,

Peeters

P.J.,

Association of SIRT1 gene variation with visceral obesity. Human Genetics.

2008;

124

(4)

:

431-6

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kilic

U.,

Gok

O.,

Bacaksiz

A.,

Izmirli

M.,

Elibol-Can

B.,

Uysal

O.,

SIRT1 gene polymorphisms affect the protein expression in cardiovascular diseases. PLoS One.

2014;

9

(2)

:

e90428

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Shimoyama

Y.,

Suzuki

K.,

Hamajima

N.,

Niwa

T.,

Sirtuin 1 gene polymorphisms are associated with body fat and blood pressure in Japanese. Translational Research ; the Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine.

2011;

157

(6)

:

339-47

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Dong

C.,

Della-Morte

D.,

Wang

L.,

Cabral

D.,

Beecham

A.,

McClendon

M.S.,

Association of the sirtuin and mitochondrial uncoupling protein genes with carotid plaque. PLoS One.

2011;

6

(11)

:

e27157

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Zheng

H.,

Fu

Y.,

Huang

Y.,

Zheng

X.,

Yu

W.,

Wang

W.,

mTOR signaling promotes foam cell formation and inhibits foam cell egress through suppressing the SIRT1 signaling pathway. Molecular Medicine Reports.

2017;

16

(3)

:

3315-23

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Gao

P.,

Xu

T.T.,

Lu

J.,

Li

L.,

Xu

J.,

Hao

D.L.,

Overexpression of SIRT1 in vascular smooth muscle cells attenuates angiotensin II-induced vascular remodeling and hypertension in mice. Journal of Molecular Medicine (Berlin, Germany).

2014;

92

(4)

:

347-57

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Zhang

F.,

Jin

H.,

Wu

L.,

Shao

J.,

Zhu

X.,

Chen

A.,

Diallyl Trisulfide Suppresses Oxidative Stress-Induced Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells through Production of Hydrogen Sulfide. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity.

2017;

2017

:

1406726

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Winnik

S.,

Stein

S.,

Matter

C.M.,

SIRT1 - an anti-inflammatory pathway at the crossroads between metabolic disease and atherosclerosis. Current Vascular Pharmacology.

2012;

10

(6)

:

693-6

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Wang

Y.,

Tong

L.,

Gu

N.,

Ma

X.,

Lu

D.,

Yu

D.,

Association of Sirtuin 1 Gene Polymorphisms with the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Chinese Han Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of Diabetes Research.

2022;

2022

:

8494502

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Xu

C.,

Wang

L.,

Fozouni

P.,

Evjen

G.,

Chandra

V.,

Jiang

J.,

SIRT1 is downregulated by autophagy in senescence and ageing. Nature Cell Biology.

2020;

22

(10)

:

1170-9

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Mariani

S.,

Costantini

D.,

Lubrano

C.,

Basciani

S.,

Caldaroni

C.,

Barbaro

G.,

Circulating SIRT1 inversely correlates with epicardial fat thickness in patients with obesity. Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases.

2016;

26

(11)

:

1033-8

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Esmayel

I.M.,

Hussein

S.,

Gohar

E.A.,

Ebian

H.F.,

Mousa

M.M.,

Plasma levels of sirtuin-1 in patients with cerebrovascular stroke. Neurological Sciences.

2021;

42

(9)

:

3843-50

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Liu

Y.,

Jia

S.,

Liang

X.,

Dong

M.,

Xu

X.,

Lu

C.,

Prognostic value of Sirtuin1 in acute ischemic stroke and its correlation with functional outcomes. Medicine.

2018;

97

(49)

:

e12959

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Liang

X.,

Liu

Y.,

Jia

S.,

Xu

X.,

Dong

M.,

Wei

Y.,

SIRT1: The Value of Functional Outcome, Stroke-Related Dementia, Anxiety, and Depression in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases.

2019;

28

(1)

:

205-12

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar

Comments

Article Details

Volume & Issue : Vol 10 No 3 (2023)

Page No.: 5575-5583

Published on: 2023-03-31

Citations

Copyrights & License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Search Panel

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Search for this article in:

Google Scholar

Researchgate

- HTML viewed - 4653 times

- PDF downloaded - 1473 times

- XML downloaded - 100 times

Biomedpress

Biomedpress